I tried a sensory deprivation tank once. I spent two hours in a completely dark room, floating in a high-buoyancy liquid as I lay back. Earplugs blocked out almost all surrounding sound. My experience wasn’t entirely silent, though; I could hear my heartbeat and the sounds I made when I splashed the water out of boredom. When the two hours ended, there was a gentle knock on the wall beside my head, signaling it was time to leave.

It is difficult to estimate how much time passes when your senses are deprived. There are some changes around you in the sensory deprivation tank, but not many. Things happen one after another: my nose itches, I scratch it, I sit down for a moment, splash some water on myself, and turn over slightly. I’m confident time is passing—or rather, I have no reason to doubt its passage, whether I’m in the tank or outside of it.

But is my experience of time passing accurate? That depends on what we mean by ‘passage’. Typically, this notion implies a dynamic flow from the past via the present to the future. I don’t believe I have ever experienced time passing in such a way. After researching time, I’ve concluded that this kind of passage doesn’t exist. However, I do think time passes. I don’t believe it’s an illusion. We just need to be very clear about what it means to claim that time passes. I will argue that time does not pass in the same way that a river flows. Rather, the passage of time is about one thing following another. Such a deflationary theory provides us with a commonsensical yet scientifically credible explanation of how time passes.

The idea that time passes has been challenged since the time of the pre-Socratics. Parmenides, for instance, argued that the concept of passage involves a contradiction and, therefore, does not exist. At least, he came close to such an anti-realist position. Some fragments of his philosophical poem, or interpretations of it by later thinkers, have survived to this day.

Parmenides believed that our ordinary beliefs are filled with contradictions. Our thinking about time is no exception. If time passes, there must be a shift from the future to the present to the past. But this implies the reality of both the future and the past, much like moving from one spatial location to another requires the existence of distinct places. The future ‘awaits’, and the past ‘lies behind’. But if that’s the case, how do past and future times differ from the present? It is tempting to say that the past and the future are not real now. After all, they are not the present. But if only the present is real, then the past no longer exists, and the future does not yet exist. Yet, we continue to think about the past and the future. How can we think about something that does not exist? This is where the contradiction arises: we both affirm and deny the reality of the past and future.

Let’s say we just stick with the mundane idea that only the present is real. We exist in the present. The past is just our memories and the future our expectations. For there to be passage of time, the non-existent future should become the now, and then this existent now should evanesce. How can something fade into nothingness, and nothing become something? As the eight fragment of Parmenides’ poem reads: “And how could What Is be hereafter? And how might it have been? For if it was, it is not, nor if ever it is going to be.”

The typical interpretation of Parmenides’s text is monistic. Reality is a complete unity devoid of any division, difference or change. To quote from the eighth fragment again:

What Is is ungenerated and deathless, whole and uniform, and still and perfect; but not ever was it, nor yet will it be, since it is now together entire, single, continuous […] And remaining the same, in the same place, and on its own it rests, and thus steadfast right there it remains.

The one and only world—our world—lacks time. Anti-realism about time is not a widely held position among contemporary philosophers of time. However, a version of anti-realism was defended by the 20th century philosopher J. M. E. McTaggart, in a classic paper called ‘The Unreality of Time’. Much like Parmenides, McTaggart argued that describing the world using tensed concepts is illogical. Past, present, and future are incompatible notions. An event must be either past, present, or future; it would be contradictory to claim that an event can occupy more than one tensed position in time. Yet that is precisely what would have to occur in case time passes.

The conclusions of Parmenides and McTaggart were purely based on logical thought. Other reasons to doubt the passage of time arose with the development of physics. Parmenides could not have known about modern physics, of course, but around the time of McTaggart’s classic article, Albert Einstein and Hermann Minkowski published their contributions that make up the special theory of relativity. This theory poses yet another challenge to the idea that time passes.

It is usually thought that relativity is consonant with eternalism, the view that the past, present and future are equally real. According to eternalism, all events are spread across spacetime. Every event between the beginning and the end of the universe, including the event of you reading these sentences, is on the same ontological footing. If eternalism is true, it could not be that the future somehow becomes the now and then drifts off into the past. Different times all exist; they do not gradually approach or become more past. The universe is a four-dimensional block, which exists unconditionally in its entirety. To see why relativity theory is hospitable to eternalism, we should work out two of its important consequences: the relativity and conventionality of simultaneity. They provide powerful reasons to reject more commonsensical ideas about time, such as presentism, the view that only presently existing entities are real. According to presentism, past things are no more, and future things are not yet. If one were to list all things that exist, those things would exist in the present. What exists, absolutely and unrestrictedly, is confined to the present time. There are no times other than the present time.

You might think presentism is self-evidently true. Only the present is real. However, there’s a catch. If you believe that ‘now’ is exclusively real, then this moment must be entirely universal. The ‘now’ must be the same ‘now’ everywhere, regardless of where we are in the universe. If this is true, simultaneity must be absolute. There would be a knife-edge present moment stretched across the entire universe, and that universal ‘now’ would be the boundary of all that exists. Everything before it no longer exists, and everything that will come after it does not yet exist. Presentism is therefore in tension with the relativity of simultaneity. If in one frame of reference two events are simultaneous, their temporal difference is zero. As different observers in general do not agree on temporal intervals, that difference may not be zero in another frame. In some other frame the events occur successively. This means what occurs ‘now’ is relative and perspectival. One observer’s ‘now’ can be another’s ‘past’ or ‘future’. The past, the present, and the future all exist. This is in contradiction with presentism, because it maintains the existence of only one of these times, the present.

In fact, even to say that simultaneity is relative and perspectival may overstate its status in special relativity. Labelling two events as simultaneous requires us to lay down conventions that the theory does not fix for us: Remarkably, given special relativity, when, in setting up a frame of reference, we assign a time – say, t = 0 – to an event, this does not yet single out any other events as ones we have to assign the time t = 0 to. What is required for assessing simultaneity is that we know how to set our clock depending on how clocks elsewhere are set. How do we ascertain that? Well, we could send a light signal from one clock to another, from which it is reflected back to the first clock. Provided that the one-way speed of light is invariant, we could infer how we should synchronize distant clocks and ensure that they show the same time.

The invariance of the roundtrip time of light is a well-known result. There is, however, no experimental way to demonstrate that light travels at a constant velocity in one direction. Many, including for example Einstein himself, maintained the one-way speed is a convention. In his popular exposition on relativity, he called it “a stipulation which I can make of my own freewill in order to arrive at a definition of simultaneity.” According to special relativity, nothing in nature fixes a definite simultaneity relation between two distant events, not even for a single frame of reference. The most drastic implication of conventionality is that there is no such thing as simultaneity. In his “Relativity and Space-Time Geometry,” Tim Maudlin notes that given relativity, “simultaneity—two events ‘happening at the same time’—is not relative” but “simply non-existent.”

Whether simultaneity is a mere convention is a matter of on-going debate. And even if it is, that does not obviously tell in favor of eternalism. In fact, should simultaneity turn out to be conventional, this might undermine one of the main arguments for eternalism. It is questionable whether we can connect events with simultaneity-slices, and then conclude that different observers have different, equally valid moments of ‘now’, which is what the classical argument for eternalism requires. Whereas the relativity of simultaneity indicates that carving up spacetime can be done in different angles, the conventionality of simultaneity indicates it cannot be carved up in any non-arbitrary way in the first place.

Even though this complicates matters, the prospects for presentism remain grim. Presentists will want the set of all true statements to include claims such as ‘A star in the Andromeda galaxy is currently exploding.’ This should be true absolutely: the ’now’ on Earth is the same ’now’ as in Andromeda. But if we take into account the relativity of simultaneity, the statement is not true absolutely, since it may only be true in some frames of reference. If we consider the conventionality of simultaneity, the statement itself is arguably not even factual.

In short, if we take the implications of relativistic physics seriously, and base our metaphysics on relevant scientific understanding, it becomes surprisingly difficult to find room for the passage of time. What occurs right ‘now’ is relative to the chosen frame of reference. Since spacetime cannot be divided into objective layers, we cannot stack them up either. There is no universal progression from earlier times to later times through the constant creation of a new ‘now’.

The four-dimensional spacetime is known as the block universe. Is it devoid of change? Are we back to Parmenidean monism? Huw Price, in Time’s Arrow and Archimedes’ Point, comments:

… people sometimes say that the block universe is static. This is rather misleading, however, as it suggests that there is a time frame in which the four-dimensional block universe stays the same. There isn’t, of course. Time is supposed to be included in the block, so it is just as wrong to call it static as it is to call it dynamic or changeable. It isn’t any of these things, because it isn’t the right sort of entity – it isn’t an entity in time, in other words.

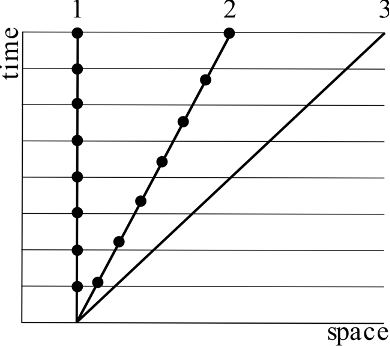

There is no time extrinsic to the four-dimensional spacetime. However, we can find time and its passage in spacetime. Hence, we are in no need to posit something inadmissible in order to argue for the existence of the passage of time. One concept in relativity is crucial for this: proper time. This is the quantity that clocks track along their path through spacetime. That path is called the observer’s worldline. Clocks measure the spacetime intervals between events on their worldline. Along these lines, things occur successively one after another. A different amount of time passes along different paths. This idea is sketched below. Three trajectories are depicted within an inertial frame. The first on the left is at rest relative to the frame. The second in the middle travels with a relative velocity of half the speed of light. The third on the right is a photon’s trajectory. The proper time is measured by the amount of ticks we see in the diagram. Along the second path, the clock only ticks seven times, whereas along the first, it ticks eight times. Along the photon’s path, the clock does not tick at all.

Tim Maudlin presents a clarifying analogy. We can think of clocks like odometers in cars. Imagine two cars with the same odometer readings at the start. They take different routes and then come back together, but after the trip, their odometer readings no longer match. The same principle applies to clocks.

This gives us a way to answer an underlying problem. If time passes, how fast does it pass? If times passes, it should pass at a definite rate, one might think. How can we measure such passage? “We do not even know”, Jack Smart remarks in “The River of Time,” “the sort of units in which our answer should be expressed.” If the answer is one second per second, well, that is not really an answer as the seconds cancel out and we are left with a sheer dimensionless number. But the passage of time makes perfect sense without needing units. When comparing trajectories 1 and 2, we can say that time passes more quickly for the first system as compared to the second, and more slowly for the second system as compared to the first. With those values, about 87 percent of the time that passes for the first system passes for the second system. Similarly, we might say that a person who is 1.9 meters tall is about 115 percent of the height of a person who is 1.65 meters tall, and the second person is about 87 percent of the height of the first. The rate of time’s passage is not compared to any supposed absolute time itself, but rather, it is a comparison between different systems in spacetime. There is no need to assume a singular time that flows at a uniform speed for everyone. This is analogous to comparing the heights of two people: there is no need to reference some absolute, body-independent space.

Critics of the passage of time are correct in pointing out that there is no literal ‘flow’ of time. Isaac Newton believed in an absolute time that flows at a constant rate, regardless of circumstance. In this view, time is like a river: we stand passively on its bank as the water flows by. But we don’t need to think of time’s passage in terms of flowing. Time passes at different rates for different travelers through spacetime. A classic science-fiction example, which aligns with scientific predictions, is this: A mother sets off on a space journey in a spaceship traveling close to the speed of light, while her infant son stays on Earth. When she returns, she is younger than her son. Time passed for both, and neither noticed any difference in their own reference frames. However, when they compare their clocks—represented here by their bodies—they find that different amounts of time have passed for each. How much time passes is relative, but the fact that time passes is not. Both are older; both have moved from earlier times to later times. I agree with Andrew Newman in his article “The Rates of Passing of Time”, as he argues that the differing rates of passage reinforce the reality of time’s passage: “Time passes at different rates along different world lines. The best explanation for these different rates is that time indeed passes.”

The idea that time itself passes from the future via the now to the past could be called an inflationary theory of time. We could be more modest and think about the passage of time in deflationary terms. According to deflationism, passage of time is the succession of events along observers’ worldlines.

Deflationism has been criticized for watering down the idea of time’s passage. For genuine passage to occur, the future must approach, turn into the present moment, and eventually fade into the past. Deflationary theory cannot accommodate this process. It holds that there are simply sequences of events, without any notion of ‘approaching’ or ‘fading away’. We can compare this to spatial separations. The coffee cup on my desk is closer to me than the coffee pot in my kitchen. However, there is no ‘passing’ of space from the pot to the cup or to me. Similarly, when I first pour coffee from the pot into the cup, and then proceed to drink it, there is a fixed sequence. Pouring happens before drinking, and drinking happens after pouring. This fixed relation does not demonstrate the passage of time.

I believe this criticism rests on a questionable assumption: the assimilation of two types of extension—spatial and temporal. It is true that the concept of four-dimensional spacetime integrates space and time, so the two cannot be completely separated. But looking at spatial and temporal extensions, they are not exactly the same. Spatial extension is static. There is no ‘passing’ of space. There are directions like ‘up’ and ‘down’, ‘left’ and ‘right’, but these are purely perspectival. Temporal extension, however, is different. As Natalja Deng explains, temporal extension is succession. Things come one after another. An earlier event happens before a later event, and a later event after an earlier event. Causes temporally precede their effects. In other words, one event follows another, and according to deflationism, this succession is the passage of time.

The deflationary account of time’s passage retains many commonsense intuitions about time. Time cannot be stopped. It is a one-way road. We constantly age, moving away from our births and toward our deaths. What is done cannot be undone. All around us, change is happening—in our minds, our bodies, and our environment. These changes serve as evidence of the passage of time.

Passage requires that temporally ordered events exist. I like to quote from Joshua Mozersky from his interview with Richard Marshall at 3:16. When Mozersky was asked whether his account of the passage of time is deflationary, he answered yes and went on to insist “that such a minimal account captures everything we need the concept of temporal passage to capture: growth, decay, aging, evolution, motion, etc.” I think this response hits the nail on its head. Growing, decaying, aging, evolving, and moving are all real phenomena. Their common denominator is change.

The passage of time is about change. There is change in us and around us. At one point, a mug is full of hot coffee; later, it’s almost empty and lukewarm. Someone once has long hair; now they do not. A student initially receives a low grade; after preparation, they improve on the re-exam. Time passes.

Matias Slavov is a post-doctoral fellow at Tampere University and the author of Relational Passage of Time (2024).