The parents of two chronically ill children can afford proper treatment for only one of them; they get treatment for the sicker one, and, with great anguish, leave the other to endure debilitating symptoms. A soldier fires into a baby carriage that is believed to be a prop being used to conceal explosives – later to discover that it was actually just holding a baby. He develops an image of himself as a moral monster – someone unworthy of human dignity – and years later he finds he cannot live with himself. An individual happens upon an assault-in-progress in their neighbourhood; they rush forward to intervene but upon glimpsing a gun in the assailant’s hand they are overcome with fear and freeze involuntarily – allowing the assault to proceed. They relive this moment repeatedly, blaming themselves for what happened. A pregnant woman is threatened by an intelligence officer; they will beat her and cause her to miscarry unless she gives up information on her husband, who is in hiding – she chooses to betray her husband and she tells them where he is. As soon as the words are out of her mouth she thinks to herself, ‘I have no integrity.’ A doctor attempts an experimental procedure without knowing the probability of its succeeding – in fact it brings about the patient’s death, for which the doctor then feels responsible. A woman escapes violent persecution and seeks asylum with her children in a safer country – but does so by abandoning her elderly parents, who were unable to make the journey with her. She lives thereafter with a sense of failure, of having violated an absolute filial duty. An aid worker distributes all of the food, water, and medications that he has, and, even while still believing himself to be responsible for meeting the needs of the dozens of people who remain waiting in line, he begins turning them away.

In some of these cases a dilemma arises because committing some wrongdoing is unavoidable: someone facing a moral dilemma is forced to choose one way of failing or another. In other cases a failure results from a person’s sheer lack of capacity to carry out some morally required action, or from their lack of knowledge about which action is the right one. In other cases, needs that give rise to a moral requirement may be inexhaustible and thus impossible to meet. In each case, it is not – or at least not fully – in the person’s control to avoid committing some kind of wrongdoing. What causes the person’s lack of control varies in each case, as does the degree to which they lack control, and this creates important differences amongst instances of inevitable moral failure. But I will focus on the common plight of those whose responsibility for moral failure is coupled with a lack of the sort of control that would have enabled them to meet the moral requirements that they faced.

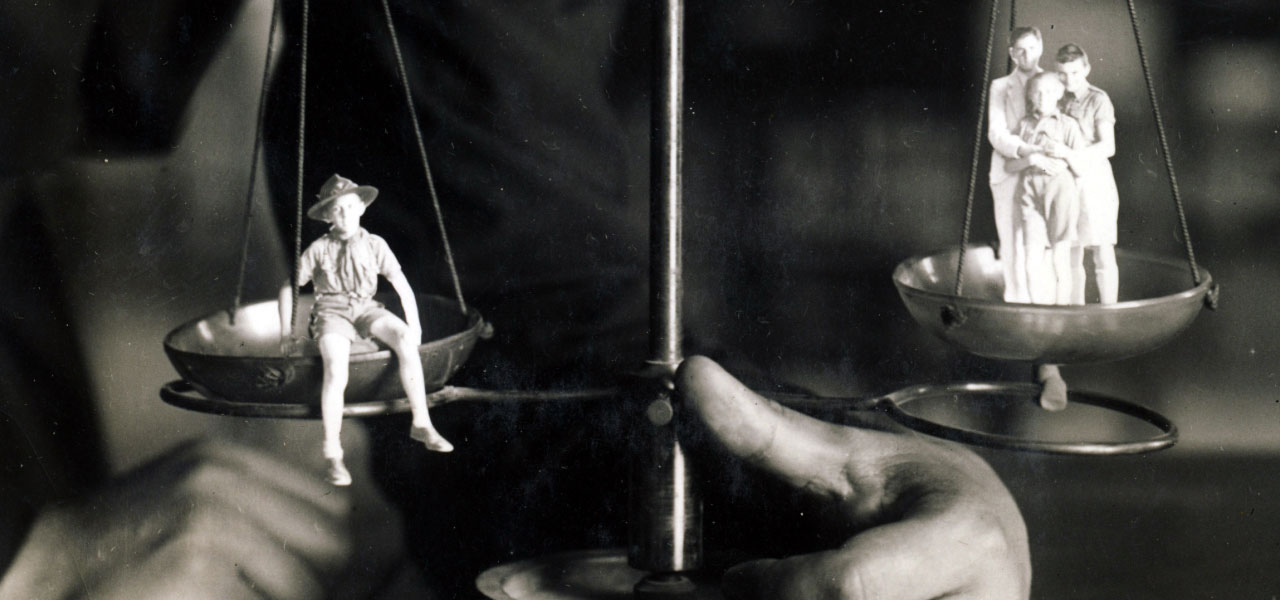

People who have committed serious wrongdoings – but who did not have it in their power to avoid them – are in a unique position: they are not in the same position as people whose wrongdoings were more fully under their own control, nor are they in the same position as people who have committed no wrongdoings at all. They are neither simply culpable nor simply innocent. The uniqueness of this position warrants some reflection, because it is hard to know how to respond helpfully to someone who is suffering in the aftermath of having morally failed in an unavoidable way; more specifically, it is hard to identify what will support or heal them as moral agents without meanwhile distorting their experience by denying the way in which they are in fact responsible for what they have done.

It is typical for people to feel a particular kind of anguish and regret (which Bernard Williams has called “agent-regret”) after having committed a wrongdoing that they were unable to avoid. On the one hand – assuming that we’re talking about decent people whose wrongful actions were at odds with what they themselves value – these emotions themselves constitute something worthy: they are the emotions that express what matters to these people, what they value. Whatever value their action violated when they committed the wrongdoing can still be affirmed and protected in some way through these emotions, and the emotions indicate that they take themselves to be responsible for a serious wrongdoing. But on the other hand, these same emotions can be psychologically devastating for whoever experiences them. This tends to lead third parties – friends of the person who has committed the unavoidable wrongdoing, or perhaps professionals such as therapists – to try to assuage the difficult emotions. The third parties often try to talk the person experiencing this sort of anguish and regret into letting go completely of their sense of responsibility, by emphasising that it was not their “fault” and assimilating their experience to that of someone who has not failed at all, morally. Meanwhile, the person themself may err in the opposite direction, treating their unavoidable wrongdoing as if it had some of the same implications as more avoidable wrongdoings have. The aim should instead be a specific form of moral repair that allows the person who has performed an unavoidable wrongdoing to grasp the unique situation for what it is: neither the same as a case of culpable wrongdoing nor the same as a lucky case of remaining innocent. This person’s sense of integrity, and their sense of dignity, can rightly be restored without their losing any of the anguish that expresses what they value, and thus without any denial that they have in fact failed morally.

The key to understanding the phenomenon of unavoidable moral failure is acknowledging something about what kind of moral agents we human beings are, as well as something about the morality that we construct, and seeing that there can be a mismatch between the two: as agents, we are very limited in what we control, what we can know, and what we are capable of; and at the same time, we construct for ourselves a morality – a set of moral requirements – that reflects not what we are able to do, but rather what we care about and what we experience ourselves as being required to do to protect what we care about. Often whatever or whomever we care about needs much more than we can provide, or is vulnerable to transgressions, traumas, or injustices that we cannot prevent, at least not without another sacrifice. We experience needs and vulnerabilities as calling out to us for a response even when responding is beyond our ability. In some cases, we might understand the requirements to respond to be (to borrow Harry Frankfurt’s characterisation of it) “commands of love”; in other cases, the social group that we live in may moralise the necessity of a response – thereby expressing what is socially valued – and we then may experience the obligation to respond as carrying the authority of morality. In any case, the experience of requirement reflects what matters to us – as individuals or as a society.

Sometimes we are up to the task of meeting the requirements that we – individually or collectively – set for ourselves. When we are not up to the task, or something prevents us from meeting the requirements, there are two possibilities. One possibility is that the losses involved are quite tolerable, or reversible, or can be balanced out by some good that we do elsewhere, and thus we can be released from the requirement. Another possibility, though, is that the losses involved are significant and irreparable, and no other values can make up for the values that are transgressed – then the prospect of failing to meet the requirements may be completely unthinkable for us. In these cases nothing can serve to release us from the unmet requirements, and they remain binding on us even if we are unable to meet them. These impossible requirements can carry the same kind of authority for us as requirements that we are able to fulfil. The philosophical principle that “ought implies can” is, in these cases, false.

The claim that we can be required to do the impossible may suggest that life is unfair; indeed, it is unfair in the sense that no one designed our lives in such a way as to ensure that we would only care about – and experience normative requirements regarding – what we can control. Good luck may help us avoid encountering situations in which we are bound by impossible moral requirements, while bad luck will put us in exactly these situations. Our attachments – our values – make us vulnerable to bad luck that results not just in loss, but also in failure: failure to protect what we value, sometimes even what we most value. These are the conditions that shape our human lives.

As human as the experience of unavoidable moral failure may be, it is not an easy experience. Just as loss brings grief in its wake, so too does moral failure bring its own set of distressed emotions. Grief expresses a valuing of what is lost. An anguished sense of regret and responsibility expresses a valuing of what has been not simply lost, but lost due (at least in part) to one’s own unavoidable transgression of the value itself. This is a specific kind of valuing: the person who values in this way takes whatever or whoever is valued to call for a response; this form of valuing is in part constituted by the grasping of a requirement. And while grief is painful, we wouldn’t tell someone who has lost a loved one not to grieve, precisely because we wouldn’t want them to deny or disavow what their grief expresses; similarly, while the distressed emotions that arise in the aftermath of an unavoidable moral failure are painful, we shouldn’t urge those who are experiencing them to deny or disavow what their anguished sense of regret and responsibility expresses, for it expresses an especially compelling form of valuing.

Nevertheless, we offer to the grieving what solace we can, and we seem to be able to do so without undermining their continued valuing of what they have lost. What solace can we offer to the unwitting and unwilling wrongdoer, without robbing them of the specific form of valuing that is partly constituted by their recognition of their own responsibility, their own failure to meet a requirement to preserve or protect or otherwise act in accordance with their values?

One problem with the way that third parties typically respond to people undergoing distress in the wake of unavoidable wrongdoing is that they tend to connect responsibility with control, and thus they either attribute to the wrongdoers more control than they had, and concede that they are responsible for their actions (perhaps even blaming them), or they recognise that the people lacked control but then deny them the responsibility that the wrongdoers experience themselves to have. Even the very person who is suffering distress in the aftermath of having unavoidably committed a wrongdoing may mistakenly equate responsibility with control. Because they take themselves to be responsible, but have no way of distinguishing their own sort of responsibility from the responsibility of someone who more intentionally willed to commit a wrongdoing, they may go too far in their self-condemnation. If they think that when people violate their own values they act without integrity, they will apply this judgement to themselves, even if their violations were not voluntarily willed. If they believe that people who voluntarily engage in terrible acts are moral monsters, they will take themselves to be moral monsters too, just because their actions were similar, despite having been impossible to avoid. They will think they are not worthy of human dignity.

The solace that we can provide may come from developing a better understanding of the moral status of unwitting and unwilling wrongdoers. A better understanding would be one that recognises that responsibility does not require complete control, so a person can be responsible for failing to meet moral requirements even if the failure was beyond their control. However, such an understanding would also recognise that unavoidable actions don’t affect a person’s integrity. If a person has integrity, they cannot violate that integrity by performing an action – even if the action violates their values – that they absolutely could not avoid. And, finally, it would acknowledge that dignity is human dignity, attaching to actual, rather than idealised, human beings. Failing due to a lack of control – which is a quintessentially human thing to do – does no damage to a person’s dignity. An understanding like this would enable us to say to someone who has failed to meet an impossible moral requirement:

- you are responsible for a wrongdoing, despite having lacked control; but

- you have not acted without integrity; and

- your dignity is intact.

However, looking more closely at what it takes to have integrity, and (separately) what it takes to be worthy of human dignity, shows how blurry the line between avoidable and unavoidable wrongdoing can actually be. Consider a case of weakness of will, namely a case in which someone knows the right thing to do, but because of some strong desire or emotion (including fear) cannot get themself to do it. We might say they are psychologically unable to stop themself from committing some wrongdoing – but we would probably say that they lacked integrity if, due to cowardice, for instance, they were simply unable to act on their values. We might take such a case to be more similar to avoidable wrongdoings than to clearly unavoidable wrongdoings. Factors that are outside of our control might be external to ourselves (like our environment, or the actions of others) or might be internal to ourselves (like our psychological traits), and we may find wrongdoings to be more culpable – and to affect our integrity – when they are due to the more internal sort of factors.

Human dignity, unlike integrity, is something that is possessed by all human beings; a person does not have to be good in order to be worthy of dignity. The most evil, culpable wrongdoers must still be treated with dignity. In this respect, avoidable wrongdoings have no different implications than do unavoidable wrongdoings. However, the person who commits an unavoidable wrongdoing violates their own values, and as a result, may feel unworthy; in a sense, they don’t treat themself with dignity because they don’t accept their own failing as part of what it is to be human. In experiencing themself as having acted against their own will – and as lacking in control – they judge themself to fall short.

We offer solace, then, by reassuring the wrongdoer that what they fell short of is an idealised conception of human agency; we only need to be actual human beings to be deserving of respect (including self-respect) for our dignity. This is a limited solace. It is as if we are saying: no, you have not acted without integrity, nor lost your dignity. But you are a great deal more limited, and less in control, than you might like to think. So are we all. And that means that we may have much to regret, for the demands of morality that we rightly apprehend may very well exceed our capacity to meet them.

I would like to thank Jan Helge Solbakk, Øivind Michelsen, and Bat-Ami Bar On for their contributions to the ideas in this essay.

Lisa Tessman is professor of philosophy at Binghamton University, and the author of Burdened Virtues, Moral Failure, and When Doing the Right Thing Is Impossible.