Should the city of Boston, Massachusetts pay reparations for its role in transatlantic slavery? This question is currently getting explored by a task force that Boston’s mayor formed in response to pressure from activists in 2022. Demands for reparations aren’t new, of course, but few people realize just how far back they go: there were already calls for reparations in Massachusetts on the eve of the American Revolution, 250 years ago, when slavery was still legal there.

Free and enslaved Black residents of Massachusetts argued for reparations at least as early as 1773, often based on the same philosophical principles that their contemporaries used to argue for American independence. The founders of the United States aimed to transcend the limits of law and imagination by aspiring to—and indeed demanding—a new, more just legal and political order. Pro-reparations activists in the eighteenth century did precisely the same. These incredible people and their arguments are largely forgotten, but we can learn a lot from them. They remind us that the call for reparations is not at odds with, but directly based on, America’s purported core values. They also show that pro-reparations activism is older than the United States itself, which present-day opponents of reparations would do well to remember when they ask, “why only now?”

In June 1773, a group of Black antislavery activists sent a petition to the Massachusetts government on behalf of all enslaved people in the province, demanding freedom and reparations. The petition was reproduced in at least two newspapers. Felix Holbrook, the group’s leader, was a prominent abolitionist from Boston who also submitted several other petitions. We don’t know much about him, but he was apparently born in Africa, enslaved as a young child, and sold to a schoolmaster in Boston, whose family enslaved him for over 25 years. He gained freedom in 1775—two years after submitting the petition. According to records of the Massachusetts House of Representatives, the legislature discussed this petition in June 1773, initially referring it to a committee and then postponing the decision to the next legislative session. It was discussed again in January 1774 and eventually resulted in a bill to ban the importation of enslaved people—rather than banning slavery itself and freeing the enslaved people who already lived in the province—without any provisions for reparations. That bill passed but didn’t take effect because the governor didn’t sign it.

Holbrook’s petition doesn’t merely demand the abolition of slavery and equal rights; it boldly declares, “we are honestly entitled to some compensation for all our toils and sufferings”. In other words, formerly enslaved people deserve reparations as compensation for the labor that was stolen from them and as damages for the harms they have suffered. Olúfẹ́mi Táíwò, in his seminal 2022 book Reconsidering Reparations, calls this type of argument “harm repair” because it focuses on compensation for specific types of harm, such as financial loss or pain and suffering.

To support their demands, the authors of the 1773 petition enumerate the moral and legal principles that entitle enslaved people to freedom and reparations. These principles include a natural right to liberty and a right “to enjoy such property as they may acquire by their industry”. There are only two legitimate ways to lose these rights, they explain: by voluntarily giving them up and by forfeiting them through a crime that the laws punish with enslavement. Since enslaved Black people in Massachusetts have neither forfeited nor voluntarily given up their natural rights, they must be freed and paid at least part of the value of their past labor. They additionally deserve to be paid damages because they have suffered horrendous harms: their enslavers have deprived them “of everything that has a tendency to make life even tolerable”, including familial ties and religious practices. On this basis, the petitioners ask the provincial government to free all enslaved people and give them “some part of the unimproved [i.e., uncultivated] land belonging to this province, for a settlement, [so] that each of us may there quietly sit down under his own fig tree and enjoy the fruits of his own labour”. In short, they demand reparations in the form of land for all formerly enslaved Black people in Massachusetts.

These arguments for reparations are forceful in part because they are based on moral and legal principles that were widely accepted by the White elites in New England, who around this time started to employ the same principles in their objections to British rule. The natural rights to liberty and private property are central to liberalism, the political philosophy co-founded by John Locke and embraced by the proponents of American independence. In this historical context, invoking these principles was an immensely promising strategy.

The petitioners’ strategy has another notable component: they stress how modest their request is, all things considered. After all, they explain, enslaved people are entitled to far more than the petition is demanding. If enslavers and their families were required to pay for the entirety of the labor they have stolen, they would be financially ruined or at least lose a significant portion of their wealth. Yet, the petitioners stress, this is not what they are demanding. They “claim no rigid justice”, that is, they do not request the full amount to which they are legally entitled. Rather, they merely ask the government to grant formerly enslaved people land that is currently unused (or rather, we might add, currently unused by White colonists, but probably used by indigenous people).

To make their proposal even more palatable, the petitioners argue that giving formerly enslaved people vacant land will have many advantages for the province. This scheme, they note, will ultimately benefit society as a whole. It “will remove all rational objections to our freedom and promises so much good to your oppressed petitioners, as well as future advantage to the province”. They were presumably thinking of several objections invoked by their opponents. One common objection against abolition was that formerly enslaved people would be unable to make a living and that they would hence either require continued financial support from their former enslavers or become a burden on society. Other objections involved racist fears of an increase in crime, social unrest, or the intermarriage and mixture of Black and White people. The petitioners suggest that giving formerly enslaved people vacant land on the province’s frontier would allay such worries—they would be able to support themselves with their own labor and, as the petition appears to suggest, form separate communities.

We find a similar idea in a fascinating philosophical text by Caesar Sarter, an African-born formerly enslaved Black man from Newburyport, Massachusetts, who may have been one of the authors of the 1773 petition. In an antislavery essay that he published in a newspaper in 1774, he addresses enslavers who are deterred from liberating enslaved people “by the consideration of the ill consequences” to themselves. In response, he stresses how wrong it is to enslave innocent people, adding that the Massachusetts government, “on our humble petition, would, I doubt not, free you from the trouble of us by making us grants in some back part of the country”.

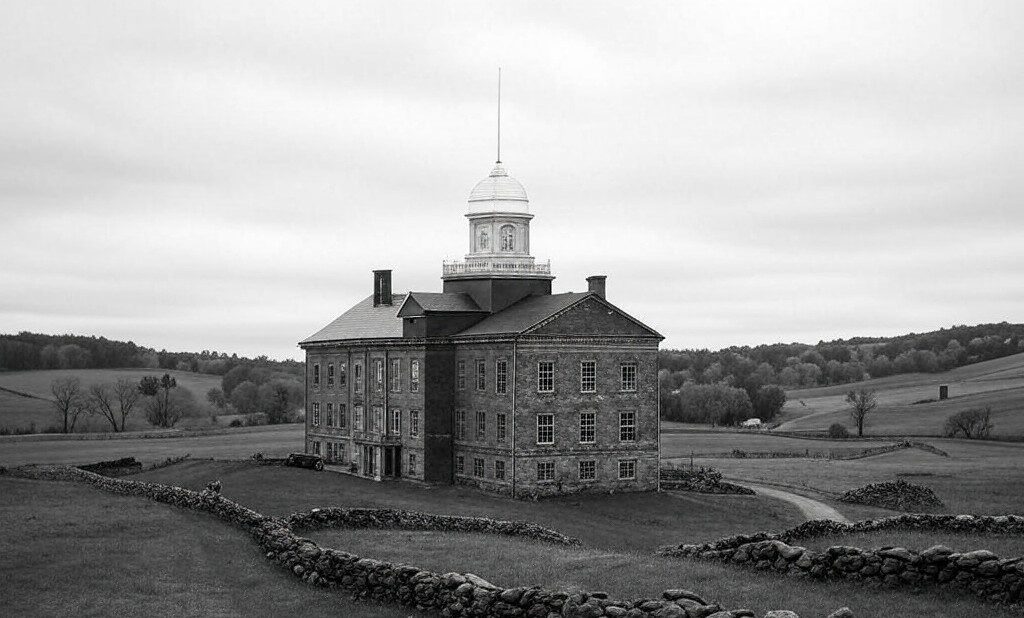

Some authors demanded cash payments, instead of land. One intriguing example is Belinda Sutton, a Black woman who was born around 1712 in what is today Ghana, enslaved as a child, and eventually sold to the largest slave owning family in Massachusetts at the time, the Royalls. When the Royall family abandoned its plantation in Medford to flee to England during the American Revolution, Sutton—already in her 60s—gained freedom. In 1783, she petitioned the Massachusetts legislature for reparations from the seized Royall estate to compensate her for her many years of unpaid labor; the manuscript is housed in the Massachusetts Archives and the text was reprinted in several newspapers. Sutton’s petition is fascinating in part because it contains an autobiography, including an account of her childhood on the banks of the Volta River, her kidnapping, and the Middle Passage across the Atlantic.

Sutton’s argument for reparations is equally noteworthy. She points out that the laws of Massachusetts “rendered her incapable of receiving property” while she was enslaved, and that she never had “a moment at her own disposal”. When she finally gained freedom after fifty years of enslavement, she explains, she was left empty-handed. Due to her age and ill health, she was unable to support herself and her disabled daughter. This, she eloquently argues, is clearly unfair: “The face of your petitioner is now marked with the furrows of time and her frame feebly bending under the oppression of years, while she, by the laws of the land, is denied the enjoyment of one morsel of that immense wealth, a part whereof has been accumulated by her own industry and the whole augmented by her servitude.”

Two things are particularly important about Sutton’s argument. First, she notes that she is entitled to payments from her former enslavers’ estate because they became rich by oppressing her and many others. The Royall family’s wealth was acquired through the labor of enslaved people. Thus, a portion of this wealth rightfully belongs to Sutton—as she puts it, “for the reward of virtue, and the just returns of honest industry”.

Second, it is notable that Sutton explicitly criticizes the “laws of the land” that don’t entitle her to any part of the Royall estate. Her petition hence has a broader scope than one might initially think. She is not arguing on the basis of current law. Rather, she is advancing a moral argument for reparations, going beyond existing law and hence contending that the current system is deeply unjust. While she explicitly asks for reparations only for herself, her argument clearly generalizes since it applies to many enslaved and formerly enslaved people.

Sutton’s petition may have been inspired by the somewhat similar case of Anthony and Cuby Vassall, a Black married couple. Like Sutton, they became free when their enslavers fled to England during the American Revolution. Anthony used to be enslaved by Penelope Royall Vassall, the sister of Sutton’s former enslaver, who lived in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Cuby used to be enslaved first by Penelope and her husband and then by their nephew and neighbor John. After gaining freedom, Anthony and Cuby remained on the estate in Cambridge that John had abandoned and that the government had seized; they inhabited a humble tenement with their children and farmed a small parcel of land, for which they paid rent. In 1780, when Anthony was already in his late 60s and Cuby probably in her 40s, they petitioned the state legislature to grant them ownership of the land they were renting, plus an additional quarter of an acre, so that they would be able to continue supporting themselves and their family.

To argue that they should be granted ownership of the land, Anthony and Cuby note that they spent their most productive years in slavery and that the revolution has “deprived them of that care & protection which they might otherwise have expected from [their enslavers]”. In other words, slavery prevented them from saving for old age and their enslavers, who would otherwise have been obligated to support them, have left the country. They add that the land they currently rent is not large enough to feed their family and that there is also a significant danger that they may lose their right to farm it. In a separate document, Anthony elaborates on just how difficult and precarious their situation is. He explains that they have a large family to support, that he is getting old, and that Cuby is currently ill. As a result, they are struggling to grow enough food. He also voices his fear “that if his house should be taken from him, and he be denied the improvement [i.e., cultivation] of the little spot of land, … that himself his wife and little ones must throw themselves upon the charity of others, be reduced to wander abroad [i.e., become vagabonds], and adopt the hard necessity of begging for a little bread”. Later in this document, he invokes ideas from the American Revolution to support his case: “though dwelling in a land of freedom, both himself and his wife have spent almost sixty years of their lives in slavery”. They hence hope “that they shall not be denied the sweets of freedom the remainder of their days by being reduced to the painful necessity of begging for bread”.

In short, Anthony and Cuby Vassall demanded reparations in the form of land: they argued that their former enslavement entitles them to a portion of their former enslaver’s estate. Their request was not granted. Instead, the state agreed to pay them an annual pension—which, incidentally, is also what they would later agree to do for Sutton.

Other activists asked for reparations of a different kind, and based on intriguingly different arguments. In February 1780, Paul Cuffe, his brother John, and five other Black men from Dartmouth, Massachusetts—whose names were Adventure Childs, Samuel Gray, Pero Howland, Pero Russell, and Pero Coggeshall—petitioned the state legislature for tax exemption. One manuscript of this petition is archived in the New Bedford Public Library, and another in the Massachusetts Archives. Paul Cuffe was a Quaker and entrepreneur, and the son of a formerly enslaved African-born Ashanti man and a Wampanoag woman. He later built a successful shipping business and became one of the wealthiest and most famous Black men in early nineteenth-century America.

The petitioners’ argument for tax exemption is twofold. First, they note that they aren’t allowed to vote and hence shouldn’t be taxed, borrowing a principle cherished by contemporaneous White revolutionaries: no taxation without representation. Second, and more relevant to the topic of reparations, they argue that “by reason of long bondage and hard slavery we have been deprived of enjoying the profits of our labor or the advantage of inheriting estates from our parents, as our neighbors the white people do”. This is significant because it goes beyond the claim that formerly enslaved people deserve compensation for the labor that was stolen from them. The petitioners point out that slavery has unfairly prevented Black families in Massachusetts from building generational wealth. Hence, even people like Cuffe, who were never enslaved themselves, have been harmed financially by slavery.

Cuffe’s petition also makes another, even more general argument for tax exemption: “we poor despised miserable black people have not an equal chance with white people”. The idea seems to be that Black people in 1780s Massachusetts are at a great disadvantage for multiple reasons, including their poverty and marginalization. This is unfair because it means that Black people aren’t just financially worse off than their White neighbors, but do not even have the same opportunities to improve their situation. The petitioners elaborate that “we take it as a hardship that poor old negroes should be [taxed] which have been in bondage some thirty, some forty, and some fifty years, and now just got their liberty, … and also poor distressed mongrels [i.e., multiracial people] which have no learning and no land”. Here again, the text mentions both direct and indirect effects of slavery. People who were enslaved for most of their adult life and hence unable to save for old age should not be required to pay taxes. The same is true for people whom slavery has deprived of educational opportunities and land ownership—which include people who have never been enslaved themselves but whose parents experienced financial hardship because of slavery.

Thus, the 1780 petition advances a much broader argument for reparations than the petitions discussed earlier. It demands compensation not just for individuals whose labor was stolen or who have suffered as a direct result of their own enslavement, but also for individuals whose financial situation and opportunities are impacted by slavery in less direct ways. Black and multiracial children born to formerly enslaved parents face difficulties throughout their lives that their White peers do not face, and the government should address this inequity by exempting them from taxation. Like Holbrook’s petition, this text additionally stresses that reparations would allow Black people to make a living whereas the practice of taxing them “will doubtless, if continued, reduce us to a state of beggary, whereby we shall become burdensome to others”.

The Cuffe petition is noteworthy in part because its main argument can still be used by descendants of enslaved people today. As Ta-Nehisi Coates argues in his influential 2014 Atlantic article “The Case for Reparations”, Black Americans today can argue that they are entitled to reparations because of the cumulative effects that slavery, Jim Crow, and other racist institutions have had on their families’ ability to build wealth across generations.

Examining requests for reparations from the eighteenth century helps us to appreciate the strength of this type of argument. Imagine a world in which Anthony and Cuby Vassall became owners of about 1.5 acres of land in the center of Cambridge in 1780, as they—very reasonably—demanded. How would this have affected the lives of their heirs? Today, real estate in Cambridge is among the most valuable in the nation. Thus, the world we are imagining could easily be one in which the Vassalls’ descendants are one of the wealthiest families in Massachusetts—like some of the White families who owned similar real estate in the eighteenth century. Now imagine a world in which Felix Holbrook’s 1773 petition succeeded: all enslaved or formerly enslaved people in Massachusetts, who numbered in the thousands, were granted sizeable plots of land as compensation for their labor and the enormous injustice they had suffered. How different would the situation of their descendants be in that world, 250 years later? How much wealth would they have been able to build? In the actual world, in contrast, Holbrook was admitted to an almshouse in 1792 and the Vassalls received a small pension that presumably did not allow them to leave anything to their children.

Activists who demanded reparations in eighteenth-century Massachusetts were often ignored or faced significant opposition. One prominent opponent was Nathaniel Jennison, a White enslaver from Worcester county. He argued in a 1782 memorial addressed to the state legislature that if slavery is abolished, it would be extremely unfair to require enslavers to financially support the people they used to enslave. If he is required “to support his Ten Negroes while they run about living in pleasure & Idleness, he is the most abject Slave that ever existed”. In other words, he contends that this requirement would violate his own right to liberty and practically make him a slave. Incidentally, Jennison was at that time the defendant in a court case for his assault of Quock (or Kwaku) Walker, one of the ten Black people he claimed to own. Jennison was convicted in April 1783, and the case is widely considered to have brought about the de facto abolition of slavery in Massachusetts. After all, the court agreed with Walker’s argument that slavery is incompatible with the 1780 Massachusetts constitution.

Some proponents of slavery went even further than Jennison and argued that former enslavers, rather than formerly enslaved people, deserve reparations if slavery is abolished. In March 1783, the Boston newspaper Independent Ledgerpublished a letter to the editors under the pseudonym ‘Equity’. The letter’s author argues that anyone who acquired enslaved people while slavery was legal should be considered the rightful owner of these people. Hence, the letter claims, it would be unjust for the government to deprive such enslavers of their human property by abolishing slavery—unless “our wise Legislators will at least order, that the legal possessors of blacks shall be refunded for their property so taken from them, without their consent”.

Black activists made extremely compelling arguments for slavery reparations in Massachusetts 250 years ago. They demanded reparations in the form of cash payments, land, or tax exemption, as compensation for the labor that was stolen from them, their pain and suffering, and to make up for the lack of generational wealth and equal opportunities of Black and multiracial families. Their arguments, and the arguments of many others who continued the fight for reparations, have not yet convinced the government. Nevertheless, those who support reparations for slavery today can learn a lot from these courageous people and their strategies. Indeed, present-day activists can use the fact that there were already demands for reparations in the 1770s to support their argument that the city of Boston, or other political entities, should pay reparations now. And even those who oppose reparations should be aware of the long and fascinating history of pro-reparations activism.

Julia Jorati is a Professor of Philosophy at the University of Massachusetts Amherst and a visiting professor fellow at Slavery North; she is the author of Slavery and Race: Philosophical Debates in the Eighteenth Century and Slavery and Race: Philosophical Debates in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries.