In my February, 2023, The Ethics of Suicide I examined my father’s illness with respect to the ethics of suicide from the perspectives of Kant’s Deontology, Mill’s Utilitarianism, and the Jain religious tradition. My father has cerebellar ataxia, which has made it virtually impossible for him to walk. He also has late stage dementia, which makes it hard for him to remember things, enjoy eating various foods, and take care of basic bodily functions. In spite of all the difficulty he faces, his will to survive is strong. He regularly points out to me that during his struggles with ataxia and dementia he has survived the loss of my mother to cancer, two types of cancer, and a major pandemic. He says that what keeps him going is the enjoyment he gets from engaging with his family and wanting to see his only grandchild become a medical doctor.

In my previous piece, I mused that if I were in my father’s situation, I might choose to end my life because of the inability to function in the world in ways I desire to. But, I also made it clear that I couldn’t be certain how likely I would be to end my life because I am not in my dad’s situation, nor have I been in any situation that is similar enough to make my musings more than speculative.

Things have changed. I have now been diagnosed with late-stage stomach cancer. The statistics say I only have a 6% chance of being alive in 5 years. The stomach cancer has already caused two strokes. I live with a gut-brain paradox. If you treat the stroke, then you might cause bleeding in my stomach. If you treat the stomach cancer, you increase the probability of a stroke. My two strokes have compromised my left hand’s functionality. I am currently undergoing aggressive cancer treatment. The doctors say that if I don’t treat the cancer, I would probably only live for another two months without debilitating discomfort.

It has always been jarring to me when a reporter jabs a microphone up to someone who, say, is being wheeled out of their still burning home and asks: “Can you tell us how you feel right now?” Umm, how do you think they feel? This is to say that this essay is not about my feelings regarding my diagnosis. Feelings are important, some would argue there is nothing more important, but that is not my focus here.

There is now no escaping the question: what matters most to me? What should I do? I cannot shake off deciding on these questions with the thought “I can always figure this out later”. Time is not on my side. Naturally some of the questions that arise have to do with what quality of life I wish to live in for the remainder of my time. We can naturally distinguish between three things, being alive to do what one wants to do, having the capacity to do what one wants to do, and having the means to do what one wants to do.

Some people are alive and have the capacity to do what they want to do. If they want to go for a walk by themselves they can do so. Some people are alive and have the capacity to do what they want to do, but don’t have the means to do what they want to do. They could physically go on a trip around the world but they lack the monetary means to do so. And then there those who have the monetary means to do almost anything they want to do, but lack the physical or mental capacity to do most things. When one thinks about the kind of life they want to live when they have a terminal illness it is clear that time till death, functional capacity, and monetary means all matter in selecting how to spend what time they have left. But there are moral questions as well.

For example, I have some time, the means, and some capacity to adopt a child during my terminal illness. Something I have thought about for a long time before my illness became known. However, I should ask: would it be moral for me to do this, knowing that I would be rendering my child fatherless in a few years? On the one hand, it seems that I could do a great deal of benefit to a child that currently lacks a family. On the other hand, I could inflict even more harm on a child that already has suffered from the lack of a stable family. Choosing how to spend one’s remaining time is not all that different from choosing how to spend one’s time. The moral questions are omnipresent.

Rebecca Chan offers a nice account of Laurie Paul’s position on “transformative experience.” On Paul’s view transformative experiences are those that radically change the person that has the experience in an epistemic and personal way. When a person transforms epistemically, they gain knowledge of “what the experience is like” that they could not have had without the experience. For instance, feeling love for the first time—be it for a romantic partner or pet—is the only way to truly know what it’s like to love. When a person feels love, that person might transform personally, or such that key agential features, like their core preferences, life goals, and way they maneuver through the world, change. While these personal transformations might be caused by epistemic ones, they could also just arise alongside the epistemic transformation as a result of the new experience. Experiences like falling in love that transform people both epistemically and personally are transformative experiences.

Evan Thompson argues that death is the ultimate transformative experience. By this he does not mean the state of being dead. Rather, he means, the whole process of dying, culminating in the end of a person’s life. He maintains that death is epistemically transformative because you cannot know what it is like to die until you experience dying and this experience enables you to understand things in a new way. He also holds that it is personally transformative because it changes how you experience yourself in ways that you cannot fully grasp before these changes happen. And he states that death is unlike any other transformative experience. It is the ultimate one, not only in being final, inevitable, and all encompassing, but also in having fundamental significance.

I agree with Paul that there is a very interesting philosophical phenomenon that we are capturing with the phrase “transformative experience. And I agree with Thompson that death is a very unique and interesting kind of transformative experience. However, my approach to death as a transformative experience has some subtle differences from how Paul defines “transformative experience” and how Thompson locates death as a transformative experience.

In contrast to both Paul and Thompson, on my approach we need to focus on the difference between coming to know about an upcoming experience and the experience itself. They are both transformative. For example, when you are about to become a parent, that knowledge in and of itself can be transformative. When you eventually have the child, that is also transformative. The coming to know prepares you for a reevaluation without saturating you in the personal project of parenting. The coming to know is consistent with failure in a way in which the experience is not. You can come to know –on non-factive accounts of ‘know’– that you will be a parent, but then have, for example, a miscarriage. You can come to know that you have a terminal illness with only one year to live and then die much earlier or live much longer.

My claim is that gaining knowledge of a terminal illness is an interesting kind of transformative experience because knowledge of the terminal illness is an entire transformative experience. By contrast, knowledge of being pregnant is often, but not always, succeeded by bringing a child into the world. It is also a repeatable experience. You can know that you are going to have a child, have a child, and then repeat the experience. If you have a terminal illness, you know you are going to die, but when you die, there is no repeating it. On non-afterlife accounts of death, death is not an experience, since the subject only exists before and at best partially during the experience, but not after the experience. Rather than death, it is the knowledge of terminal illness that one lives through. It is living with the knowledge of impending death that structures how the knowledge transforms one.

The temporal dimension of ‘terminal’ illness is central on my view. We are all going to die, and thus in some sense we always live with the background knowledge that death could come about at any moment in innumerable ways. The terminality of one’s knowledge of terminal illness does not disrupt either of those facts. One can come to know on Monday morning that they have a terminal illness that will lead to their death in six months, only to be hit by a bus on Monday afternoon, while leaving the hospital. The knowledge of terminal illness transforms one not by disrupting the background knowledge, but by bringing into relief the background knowledge as it calls out for one to reflect on their life project(s). Knowledge of terminal illness is intimately connected to the personal aspect of transformative experiences. We all know from a third person perspective that we will die at some point. We just don’t know when. We also reasonably believe that those older than us are likely to die before us. However, none of this third-person perspective knowledge puts us in an intimate relationship with our own death. The terminality of terminal illness gives us an imminent phenomenal first-personal acquaintance with an impending state of affairs. The knowledge of this terminality, given that it concerns final existence, is deeply transformative.

My friend Victor Pineda runs a foundation named after him, co-titled – “A World Enabled”. Victor has collagenopathy type 4. His condition has been with him since he was a child. We went to high-school together and have remined close friends for 30+ years. Victor is an inspiring person. Although he is confined to a wheelchair, and requires a breathing machine to help him breathe, he has unbounded energy and creativity. His resume is awe inspiring. About 8 years ago, amidst personal reflection on his career and his relationships, he started making a film focused on the question: what is a life worth living? Knowledge of a terminal illness leads to this question as well because of the intimate connection that one has temporally to the time they have left. In 2016 we met near the Taj Mahal to discuss his film and the direction he wanted to take. Any creative project goes through many revisions. It has been amazing to see how Victor has transformed in his reflections on the question through working on this project. The core of his film in its exploration of a life worth living has not really changed. What grew out of his deep personal and philosophical exploration was a deeper understanding of the kinds of answers one can give to the question. As a professor of philosophy for 25 years I can say easily that one of the greatest philosophical breakthroughs is seeing that there are more types of answers to a question than one initially imagined.

Just as we can inquire into what quality of life we want to live in the time we have remaining we can also ask what continuation of one’s current life is worth suffering through. In some sense all life is suffering because of impermanence, at least the Buddhist say so. We can ask: what suffering is worth undergoing? And when we ask the question what is a life worth living, we need to transcend the individual. My dad clearly thinks the question of what suffering is worth undergoing is answered by who he is living for, his family and grandchild. His inability to do most activities is a suffering he can undergo because he is living for his family. The worth does not derive from an activity but from the existence of a group he strongly identifies with and derives meaning from. For many people questions of existence are answered not by what, but by for whom. In my conversations with Victor, I have come to see the importance of this dimension of how one can answer the question: what is a life worth living? I agree that the for whom is central to figuring out what a life worth living is. While my family brings me great support and I love them dearly, the for whom for me is more widely drawn, including those with whom I have shared goals, values, and history.

Knowledge of my own terminal illness does not make my earlier musings about suicide that much clearer. Nor does it make me firm in a commitment to it being part of my path. It is clear to me that I prefer to exist without lots of pain, with the capacity to take care of basic bodily functions, and with the capacity to use my mind. What is unclear is how much pain and lack of basic functioning I can endure with the hope of possibly recovering those capacities or finding new ways of being. Victor often points out that technology can be liberating and enabling for those for whom the world is often not designed for. Perhaps, in the near future, a chip implanted in a brain can help those that have suffered from a stroke and consequently lost some physical functioning. Perhaps, my wife will yet get her wish, and we will die together, a very long time from now, and preferably on Mars.

What has become salient to me through my knowledge of terminal illness that is a transformative experience is that I don’t have time for all the projects I want to do. I have to decide, for example, what philosophical tasks I want to accomplish in the time I have. One way to put this is: what self should I favor continuing? The one that wants to write On Certification, connecting Indian and Analytic epistemology, or the one that wants to write The Scope of Moral Concern, connecting moral rights for non-human life with AI?

The first project speaks to my goals to bring Indian philosophy into conversation with Analytic philosophy by introducing a concept from Indian epistemology that sits between non-factive justification and factive-knowledge. The concept is housed within an epistemic architecture that is not found in Western epistemology and that could influence how epistemology is explored in a global cross-cultural and multi-disciplinary context. I take inspiration for this project from Gaṅgeśa, the 14th century father of the Navya-Nyāya school of Hindu philosophy. I believe that work in the Nyāya tradition has much to offer contemporary epistemology. What I find interesting about the concept of certification is that there is a difference between knowing because a subject satisfies some objective mind-to-world relations, for example through perception, and being certified in knowing because a subject satisfies some mind-to-mind relations in a context of social exchange where the issue of being certified as a knower is being debated. The distinction strikes me as important for diagnosing many problems in applied epistemology and for rethinking the foundational distinctions in epistemology as Wittgenstein did in his On Certainty.

The second project speaks to my desire to critically question sentientism – the view that either phenomenal or affective consciousness is necessary for moral standing and an emotional life. Many western and eastern philosophers find sentientism to be the foundational answer to the question: what has intrinsic moral standing? One can find the view in Jaina philosophy and in the work of David Chalmers. While I agree that this is the most compelling answer on the table. I find that it is too often presented without critical reflection. My research on non-human life and emerging artificial intelligence models has spurred my interest in exploring whether computational intelligence that is tied to the satisfaction of survival goals, but not essentially tied to phenomenal consciousness, is the ground of moral standing. Phenomenal and affective consciousness are grading properties that speak to the issue of why one thing matters more than another, but they don’t speak to the issue of why something has intrinsic moral standing. Simply put, I’m interested in the claim that something can be a welfare subject without having consciousness.

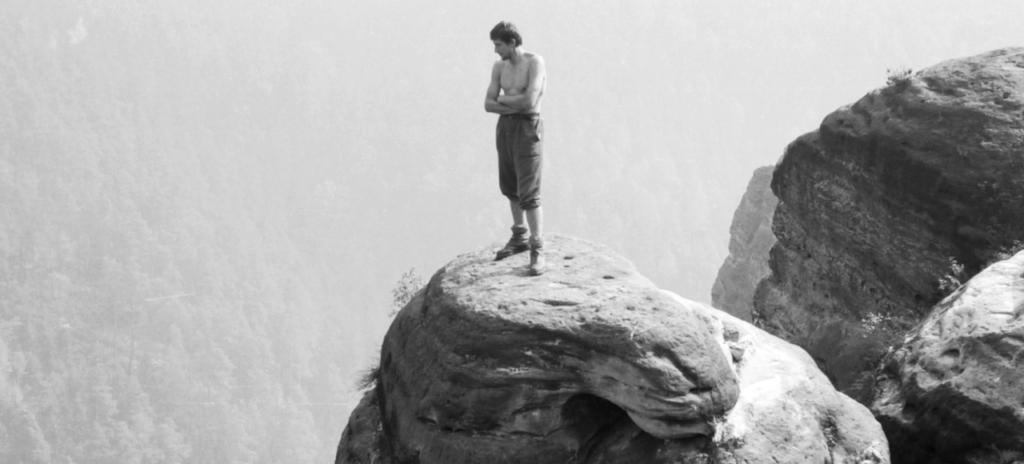

I am not certain that my ideas in either of these projects will terminate in profound philosophy, but my motivations here are philosophically honest. Still, might it now be time to focus on personal projects and accomplishments outside of intellectual pursuits? For example, going to Patagonia or hiking the John Muir Trail with my wife? How does one decide such things?

The temporal dimension of terminal illness is salient and it matters. How much time one has matters for what they can accomplish. There is an urgency that is neither diminished by working faster nor more often. Because the urgency concerns finality, without further qualification.

Anand Jayprakash Vaidya is professor of philosophy and occasional director of the center for comparative philosophy at San Jose State University. His interests include critical thinking, epistemology, and philosophy of mind from a cross-cultural and multi-disciplinary perspective.

Pingback: Anand Vaidya (2024) - Daily Nous

Rest in peace, Anand (10/11/24)

Goodbye, Anand. You were beautiful, inside and out. Love you, brother. See you in the great beyond.