In the modern workplace context, “severance” naturally evokes the idea of the compensation or benefits one might receive upon being terminated or laid off from their job. But in Severance, a mind-bending new Apple TV+ show that recently concluded its first season, the idea has nothing at all to do with leaving a job. In fact, as the story unfolds over nine riveting episodes, we see that, in fact, quite the opposite is true.

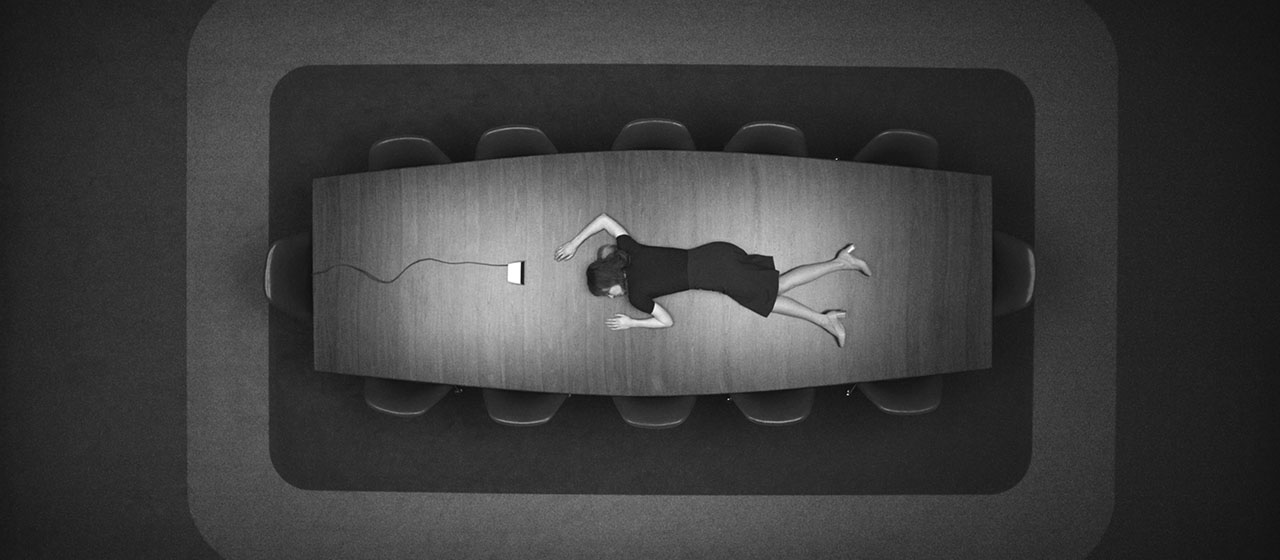

“Severance” refers to a novel medical procedure that employees at Lumon Industries, a vague and mysterious tech-adjacent company, voluntarily undergo to irreparably separate their work selves – or, in the show’s terms, one’s “innie” – from their non-work selves – their “outie”. Upon arriving at work, a severed employee transforms from their outie to their innie: in an instant, all knowledge of their families and relationships, their hobbies, their interests, and anything else related to their life outside the office is temporarily wiped from their minds, and they regain all of their work-related knowledge and memories, such as the specifics of their job, their colleagues, and so on. Then, at the end of the day, they undergo the same process in reverse: all work memories are temporarily erased upon leaving the office, and one resumes one’s outie self again, reacquiring all their memories, knowledge, and desires.

There are several benefits to undergoing severance. For the employee, it affords their non-work self the opportunity for a true work-life balance – to definitively “leave work at work.” And for the employer, it prevents employees from divulging company secrets – a kind of surgically induced non-disclosure agreement. There are also individual-specific reasons for undergoing the procedure. For our main protagonist, Mark (played by Adam Scott), severance offers a temporary reprieve from grieving his late wife, since for eight hours a day, his outie – the one with memories of his late wife – is replaced by his innie, who has no knowledge of her existence at all.

While the innie and outie occupy the same body and know of the other’s existence, there is no mental overlap between them. In other words, there is physiological continuity, but no psychological continuity. This demarcation of psychologies introduces not only the primary source of narrative conflict, but also the central philosophical puzzles surrounding the severance procedure.

The first of these concerns personal identity: are the innie and outie the same person? Those who think physical continuity is all that matters to personal identity would of course answer yes. But surely the total lack of psychological continuity between innies and outies pushes us strongly in the opposite direction. The fact that their memories, self-conceptions, desires, relationships, and so on are, by design, completely distinct forces us to see them as different people, despite sharing a body.

So, the severance procedure yields two different people – the innie and the outie. But notice that it was only the outie who chose to undergo the severance procedure; the innie was the resulting person created by the procedure, but did not themselves consent to it. Thus, while whether to undergo the severance procedure might initially seem like just an issue of bodily autonomy, it actually raises questions about the ethics of creating people. Normally, this issue centres on the more familiar forms of procreation, like creating children; but these questions can also arise when the person created is like Mark’s innie – a middle-aged, spatially and temporally limited being.

Here is an intuitively compelling principle: it is morally wrong to create people whose lives will be devoid of autonomy and not worth living. In general, this principle is easy to satisfy: we typically expect that most people will eventually have autonomy over their lives, and we have good reason to believe that one’s life will be worth living.

But what about for innies? Do innies have meaningful autonomy? Is the life of an innie worth living? On one hand, many innies seem relatively content at work. For example, Mark’s colleague Irving (played by John Turturro) often seems positively delighted to be at work; Dylan (played by Zach Cherry) often seems to enjoy himself as well. If innies tend to be happy enough at work, we might be tempted to think their lives are good enough to justify creation.

But there are also many reasons to doubt this. First, innies clearly have no meaningful autonomy over their own lives. There is practically nothing they can do to escape their fate; such power lies, it seems, only with one’s outie. Their life consists only of work, over which they have almost no control. The benefits of their labour accrue entirely to their outie. They are, in this way, a kind of slave to their outie. And it is wrong to create a slave.

This lack of autonomy also significantly restricts innies’ well-being. Innies are essentially incapable of developing meaningful, lasting relationships. Indeed, the colleague relationship is all that is available to them, and even that ends permanently if the employee leaves – as was the case with ex-Lumon employee Petey (played by Yul Vazquez). Innies are also unable to develop physically intimate relationships, despite their desire to do so – as we see between Irving and Burt (played by Christopher Walken). Furthermore, since innies’ lives consist only of work, there is no space for life projects or pursuits, hobbies and interests, recreation, or leisure. On certain objectivist views of well-being, even if innies are relatively happy – and, again, it seems that many of them generally are – their lives are not going well.

Put simply, an innie’s life is one no one would ever wish for themselves. Creating an innie involves creating a distinct person, and that person’s life is utterly lacking in autonomy and plausibly not worth living. Since it is wrong to create such a life, it is wrong to undergo the severance procedure.

While certain of the problematic features noted are exacerbated by aspects of Lumon’s climate and culture, all of them are an inevitable consequence of the severance procedure in its current form. Thus, this conclusion will hold for any company that uses this procedure on its employees. Severance, as such, is morally wrong.

This conclusion raises further complex ethical questions. Given that they’ve created a life not worth living, should outies seek to end the lives of their innies – say, by resigning on their behalf from Lumon? This raises vexing issues of killing an innocent person without their consent. As we can see, for certain innies, this would be a welcome death: they’ve even explicitly requested it. But in the absence of such a request, what is the morally right thing to do?

Is the innie justified in voluntarily ending her life, knowing that doing so will also end the life of her outie? Our judgment of this will turn, in part, on whether we think the outie is liable to this harm, on the basis of having wronged the innie through creating and perpetuating their ongoing circumstances.

The innies’ revolt in the final episodes of season one – and the ensuing chaos – prompts us to confront complex philosophical questions of how to understand personal identity when the two separate individuals merge, for a time, back into a single person. And how do our answers to the previous questions change in light of this newly formed blurriness between previously distinct selves?

Should the non-severed fight to prohibit the procedure? The protesters we encounter in the show seem fixated on Lumon’s secrecy. But surely the fact that innies are essentially slaves is the greater concern, and should be enough to justify banning severance altogether, regardless of the standards of transparency in place. We’ll find out more about the rebels, and whether they’re successful, in season two.

Whatever one’s judgment of these questions, it is clear enough that Severance raises rich philosophical puzzles that highlight and challenge our existing conceptions of personal identity, the ethics of creating people, and other related issues. For this reason alone, Severance has earned its place among other classics of philosophical film and TV, such as The Matrix, Black Mirror, and Gattaca. To be sure, its value is not merely in illuminating the philosophical questions I’ve been discussing here: Severance is a clever, innovative, and darkly funny satire of the modern workplace, our increasingly alienated culture, and the search for meaning and connection.

Dr. Jeremy Davis is an assistant professor in the department of philosophy at the University of Georgia. His research is in applied ethics, with a recent focus on questions surrounding the ethics of emerging technologies.