January 1, 2026

On the tercentenary of Kant’s birth, 22 April 2024, J. L. H. Thomas recalls a visit to Königsberg-Kaliningrad.

Kant’s home town of Königsberg, the present-day Kaliningrad, lying at the south-eastern corner of the Baltic, was founded in 1255 by the Teutonic Knights, who had been invited by the Polish prince of Mazovia to colonise the area and convert the indigenous Pruteni. The site, known in Old Prussian as Tuwangtse, was renamed Königsberg (King’s Hill), according to tradition, after King Otakar II of Bohemia, who took part in the campaign (although it may also simply be the German equivalent of Mons Regis, a Latin name given by the Teutonic Order to its castles in Palestine). At the Reformation, East Prussia, as it subsequently became known, was secularised to become the first Lutheran state, and the Grand Master of the Order created duke. A century later, the duchy was inherited by the Electors of Brandenburg, who extended the name Prussia to the rest of their domains, and in 1701 the Elector crowned himself King in Prussia in the castle of Königsberg (since it lay outside the jurisdiction of the Holy Roman Emperor). Save for an occupation by the Russians during the Seven Years’ War (when Kant applied unsuccessfully in 1758 to the Tsarina Elizabeth for the vacant chair of logic and metaphysics) and another by the French during the Napoleonic wars (when the city became the cradle of the national uprising and subsequent Prussian reforms), Königsberg remained a residence of the Prussian kings and German emperors until the fall of the monarchy in 1918, and the capital of East Prussia until the end of the Second World War. It was then destroyed by the Allies, the German population expelled, East Prussia partitioned between Poland and the Soviet Union at the Potsdam conference, and Königsberg, which became Russian, renamed Kaliningrad after a president of the Soviet Union unconnected with the city, who died in 1946. As a naval base, Kaliningrad remained a closed city during the Soviet era, and only became accessible to foreigners in 1991 following the dissolution of the USSR : it now forms a Russian exclave, separated from the rest of Russia by Latvia, Lithuania, and Belarus.

I had long wished to visit Kaliningrad on account of its associations with Kant, who spent virtually his entire life there from 1724 to 1804, and in July 1998 had an opportunity to do so whilst returning to Britain overland from a six-week stay in St Petersburg. Since my Russian visa was not valid for the province of Kaliningrad, I was advised either to fly there or else brazen it out, and I chose the latter course. In the event, after a 700-mile, eighteen-hour overnight journey by rail (on the standard European gauge) through Latvia and Lithuania, of which I saw only the border officials on patrol at the stations in their Ruritanian uniforms, I was briefly questioned at the Russian frontier, told to get a visa next time, and allowed in. Of the remainder of the journey, I recall only a number of large German-built farmhouses apparently standing empty amidst uncultivated fields.

Through the recommendation of a friend in St Petersburg, I was met on arrival in Kaliningrad by a Russian family, who gave me every assistance and assured the success of my visit : as a consequence, although spending barely thirty hours in the city, I was able to visit all the sites associated with Kant, such as they are, and gain a good overall impression of the city. Königsberg had been almost entirely destroyed towards the end of the war by the RAF and Red Army in turn, and but for a few streets in the vicinity of the main railway station, which was unharmed, the plan of the city had been much altered. The few other buildings I saw which had survived the war and the destruction of the Soviet era included the former commodity exchange, now a cultural centre for sailors, a hospital which had been turned into a naval cadet school, the cathedral, and a few other churches, one of which was used as a concert hall and another as a puppet theatre.

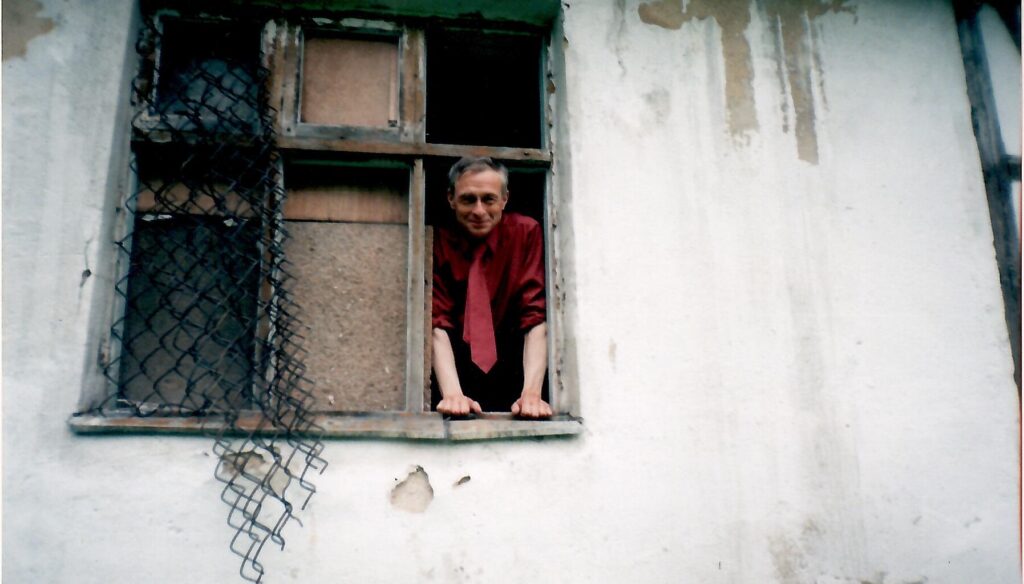

I was first taken to see the one building still standing said to have been occupied by Kant, a small one-storey, half-timbered house amongst gardens at 200 Prospekt Pobedy (Victory Avenue)in an outlying western suburb. On the strength of illustrations I later found in a German book, I identified this as a cottage beside the Forester’s House of Moditten, situated about 4½ English miles from Königsberg, in which Kant, according to his first biographer Borowski, had in his younger years often spent a week or so during the vacation at the invitation of the chief forester, Wobser, and there wrote his Observations upon the Feeling of the Beautiful and Sublime in 1763. The house, which, I was told, now belonged to the city council, had a new roof, already damaged : the door was locked, but I climbed in through an open window only to find the place derelict. I subsequently learned to my disappointment that the original Kanthaus (Kant-House) had been destroyed in the war, and that what I had seen was a replica erected by the Russians, what is more on the wrong site, the correct site being identifiable by its location with respect to a railway embankment.

I later visited the centre of the old town lying on an island in the river Pregel, which we reached across the Honigbrücke (Honey Bridge), one of the three surviving bridges of the original seven, which had been the subject of the celebrated problem posed by the citizens of Königsberg, whether it was possible in the course of a walk to cross all seven bridges once and once only, and solved in the negative in 1736 by Euler, the celebrated Swiss mathematician living at the time in St Petersburg, by means of new topological methods. With the exception of the cathedral, the entire quarter, including the original university buildings used in Kant’s day, had been razed to the ground, and in its stead now lay a rather featureless park.

Against the north-eastern outside wall of the cathedral and former university church lies Kant’s grave, the Stoa Kantiana, which was little harmed in the war and had recently been renovated. At his death, Kant was buried in the Professors’ Vault within the church, the last professor to be so honoured ; in 1880, at the time of the Kantian revival, an individual memorial chapel had been erected outside the cathedral, which was replaced on the bicentenary of Kant’s birth in 1924 by the Stoa on the same site. The modern memorial is a colonnade of thirteen lofty square columns in a reddish stone to match the brickwork of the church, with a flat roof, wrought-iron work between the columns, and a gate giving access to the grave, raised a couple of feet above the ground by two steps, on which were lying some flowers when I saw it. On the rear wall of the stoa behind and above the grave, in black lettering within a black border, is the simple inscription, IMMANUEL KANT / 1724-1804. I had read in German sources that the grave had been vandalised in 1950, but Mr Igor Odintsov, the engineer in charge of the restoration of the cathedral, assured me that Kant’s remains below were untouched.

The cathedral itself, which had burnt out completely in 1944 leaving only the walls standing, was in course of restoration by the Russians, assisted by a specialist German firm. The characteristic, rather squat spire on the south tower had already been re-erected in 1994, and the roof was also replaced shortly after my visit. It was not intended to restore the cathedral as a church, but rather for use as a concert hall and other secular purposes ; instead two chapels, one Orthodox and one Lutheran, had been dedicated under the two west towers. In the upper rooms of the north-west tower was a museum of Königsberg with particular emphasis upon Kant, to whom on the top storey had also been dedicated a memorial room, heavily carpeted and dimly lit, containing nothing but a bust and death mask : the room had been the subject of much criticism, and I, too, found its pseudo-religious atmosphere in poor taste and out of keeping with Kantian ideas. Plaster medallions of Kant as well as historical postcards were on sale below.

In the course of my visit, I learned that in the German town of Duisburg in the Ruhr, where many refugees from East Prussia had settled, there was a Museum Stadt Königsberg, and three years later I visited that also. Kant naturally had pride of place in the excellent collection, which included a portrait in oils by Doebler of 1791, and even a lock of the philosopher’s hair. The museum also provided a meeting place for an association of former citizens of Königsberg and their families, who kept the memory of the city alive, and issued a newsletter, Prussia, of which I was kindly given a largely complete set of back numbers, containing a great deal of valuable information about Königsberg. (The Museum Stadt Königsberg in Duisburg was dissolved in 2017 and its collection transferred to the Ostpreußisches Landesmuseum in Lüneburg.)

On the afternoon of my second day in Kaliningrad, through the good offices of my hosts, I had the pleasure and privilege of meeting the professor of philosophy there, Leonard Kalinnikov, a most agreeable and characterful man, who was kind enough to speak Russian to me slowly and clearly, so that I understood nearly everything he said. It would not be strictly correct to regard Professor Kalinnikov as one of Kant’s successors, since the German Albertus Universität, founded in 1544 by the first duke, Albrecht, had closed in 1945, and the Russian Kaliningrad State University (now the Immanuel Kant Baltic Federal University) was created in 1967 in succession to a pedagogical institute founded on the site in 1948 ; but he was the next best thing, and as president of the Russian Kant Society did much to promote the Kantian heritage of the city. He had been professor at Kaliningrad, I learned, for over thirty years, and had once nearly lost his post when he organised a student protest against the demolition of the castle of Königsberg in the late 1960s during the Brezhnev era : on account of his youth and inexperience, however, he was permitted to retain his chair but expelled from the Party, whilst his students were sent down from the university. Of the castle, where Kant had once worked as sub-librarian, nothing visible apparently now remains but a short stretch of wall on which has been placed a replica of a plaque which had formerly stood there bearing the celebrated words from the conclusion to the Critique of Practical Reason, now in both German and Russian : Two things fill the mind with ever new and increasing admiration and reverence, the more often and intently thought concerns itself with them : the starry heavens above me and the moral law within me. On the site of the castle had been erected a lavish, but unfinished Dom Sovietov (House of the Councils, or Town Hall), a high-rise building now owned by a South American company. I was told that it had been proposed to demolish the cathedral likewise, but this had not been done, since it would have entailed destroying the monument to Kant too, who was deemed to have been a progressive thinker and forerunner of Hegel and Marx: thus, as Professor Kalinnikov put it, Kant saved the cathedral, and the cathedral saved Kant. What Kant himself, who in later life never set foot inside the building, would have made of that – other than perhaps subsume it under the category of Community or Reciprocity in his Critique of Pure Reason – is a moot point.

Professor Kalinnikov then took me on a tour of further sites associated with Kant. The site of the house in which he was probably born, Vordere Vorstadt (Inner District) 195 at the corner of the Sattlergasse (Saddlersgate), was now a piece of open land behind a block of flats at 40 Leninskiï Prospekt (Lenin Avenue). A little further south, I was shown the site of the Haberberg church, now an arts centre, on which, partly at Kant’s instigation, the first lightning conductor in Königsberg was installed in 1784 ; I also understood it to be the church in which Kant was baptised, although in German books the baptismal entry is reproduced from the registers of the cathedral congregation. All the other houses occupied by Kant have vanished : in particular, the site of the house which Kant owned towards the end of his life at 3 Prinzessinstraße (Princess Street), later Kantstraße in the Altstadt (Old Town) now lies under a car park near the castle and the Hotel Kaliningrad, where I was staying. The house, of which a full description survives and a model was placed in the museum, had already been demolished in 1893, whilst the statue of Kant by Rauch, which had stood in front of it since 1864, was moved in 1885 to the Paradeplatz in front of the new university building of 1861. The statue had disappeared at the end of the Second World War, despite being removed to the Dönhoff estate for safe keeping, but was later recast from the original mould in Berlin, and re-erected on a slightly different location further east in front of the State University (the latter incorporates one wing of the original German nineteenth-century building, the Liebenthal Wing, which I did not see). Professor Kalinnikov and I also walked along the Philosophenweg (Philosophers’ Way) round the formerSchlossteich (Castle Pond), now a boating lake, where Kant himself had often walked.

Although German visitors were much in evidence in Kaliningrad, I had thought that I might well be the first Briton to visit the city since it became accessible. Professor Kalinnikov mentioned, however, that three years previously Lord Murray of Edinburgh had visited him : so on my return home I wrote to Lord Murray, a former teacher of moral philosophy and Lord Advocate of Scotland, and we met to compare notes. He had visited Königsberg in the course of extensive researches intended to substantiate Kant’s belief in his Scottish ancestry, and we corresponded at length on the issue. I boldly assumed the role of devil’s advocate, maintaining that Kant’s belief had been refuted by German scholars, who had traced Kant’s forebears back through three generations to the early seventeenth century in the village of Kantweinen (now Kantvainen in Priekulė) fifteen miles south-east of Memel in Courland (now Klaipėda in Lithuania) ; two of his paternal great-aunts had married Scotsmen, however, one by the name of Carr or Karr, which is probably what misled Kant, who in any case possessed little sense of history.

After my return home, I also corresponded with the Imperial War Museum in London concerning the destruction of Königsberg by the Royal Air Force during the Second World War. From the documents kindly sent me and others, I learned that Königsberg, an important supply port for the German Eastern front then about 100 miles distant, had been bombed twice on the nights of 26/27 and 29/30 August 1944 by some 800 aircraft, operating at an extreme range of 950 miles, which dropped nearly 1,000 tons of bombs, two-thirds of them new phosphorus incendiary devices linked by chains, which caught in the rooves. Nearly half the built-up area, about 20% of industry, and nearly 50% of housing were destroyed, killing at least 4,200 civilians and rendering a further 200,000 homeless out of a total population of about 370,000. The fact that the cathedral and several other churches were not directly hit, and that the castle was only partly damaged, suggests that these were avoided ; on the other hand, there was surely no reason to destroy the old town, and the relatively small impact upon industry, and the strategically inexplicable fact that the main railway station was untouched, makes it doubtful that, despite the claims made for them, the attacks, even in purely military terms, were justified by their results. On 9 April 1945, the Red Army took Königsberg after a two-month bombardment and a three-day battle, completing the destruction of the city ; again, there seems to have been no imperative military reason to capture it : the Germans were already well on the retreat, having been driven out of France in the West and much of Poland in the East, so that Königsberg, which had been declared a Festung (Fortress), could simply have been invested and left to surrender at the end of the war, like the French ports of Lorient and St-Nazaire. I am now convinced, therefore, that the motive for the destruction of Königsberg was political, not military : Stalin wanted the Prussian associations of the city to be destroyed before taking it over (although this had yet to be agreed by the Allies), and the RAF did the job for him. This would explain why the railway station was spared ; the cathedral and other churches were probably avoided through religious scruple of the air crews. The use of phosphorus incendiary bombs, principally responsible for the destruction of the city, is now forbidden under the Geneva Convention.

Although my visit to Kaliningrad was naturally of the greatest interest to a philosopher, it was also very sad to contemplate the virtual annihilation, and that largely at the hands of my own countrymen, of what had plainly been a very fine city with a crucial role in the political and cultural history of Europe : indeed, there can scarcely be another major centre of population so thoroughly devastated by the war and its aftermath. All in all, I felt that the Russian city of Kaliningrad could not be identified with the German city of Königsberg : there is no continuity of population, the cultural tradition has been interrupted, and the few remaining German buildings are little more than museum pieces. Although many of the Russians are plainly not at home in the city, there seems to be little or no interest in regaining Königsberg amongst Germans (except those born there), who evidently now prefer economic to political domination. There is in fact a long-standing rumour, never denied, that following the dissolution of the Soviet Union the Russians made an offer, which was declined, to sell Kaliningrad to Germany. The administration of the region would certainly present at least as great difficulties to Germany as to Russia ; but should the Germans ever repossess the city, they might rebuild the castle, as in Darmstadt, and conceivably also the old town, as in Nuremberg. The only consolation I could finally derive from the destruction of the city of Kant was that it afforded proof (were proof required) that philosophical ideas outlast bricks and mortar.

Mr J. L. H. Thomas is an independent professional philosopher with a long-standing interest in Kant, who has taught at Oxford, Heidelberg, Newcastle upon Tyne and Neuchâtel, Switzerland . His book, En quête du sérieux, was published in 1998.