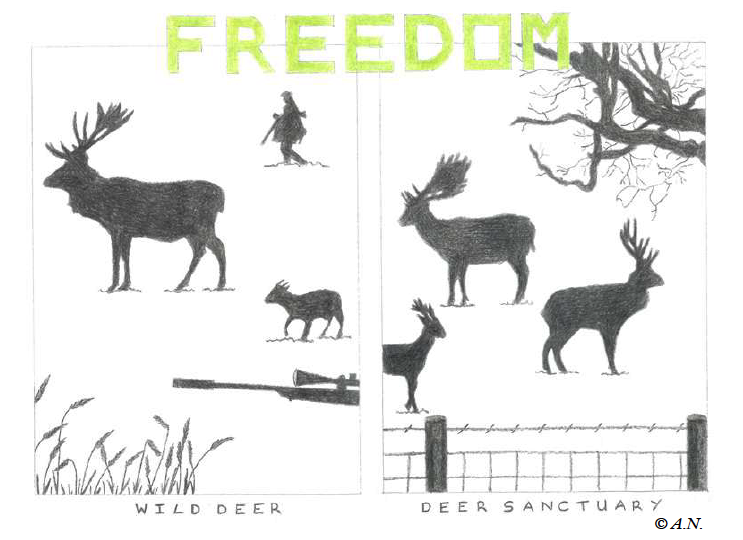

We are presented with a diptych. In the left-hand panel a herd of deer roam freely in the wild. But their freedom is not without consequence: silhouettes of hunters stalk the background and the barrel of a rifle emerges ominously from the side of the frame. The right-hand panel displays another herd. This scene is tranquil and free from hunters. But there is another trade-off: these deer are penned in, surrounded by a fence.

The images are striking, evoking a host of questions. Are we right to suppose that the deer in the wild are free, given that they are being stalked? Perhaps we should say instead that the two herds enjoy different types of freedom: one the freedom to go wherever they please, the other the freedom from being hunted. But if that’s right, which herd is better off with respect to freedom? And how should we weigh freedom against other values, such as safety and security?

The diptych is modest in its presentation. Colouring pencil on thin, white paper, hastily taped to a whiteboard in a dimly lit and grubby room. Nevertheless, it has been carefully and precisely constructed, both artistically and philosophically. This juxtaposition – a thoughtful and thought-provoking piece of work, emerging from an otherwise dull and debilitating environment – strikes to the heart of our experience doing philosophy in prisons. The picture itself is one of over 20 philosophical projects to have been created by three groups of men in a large category B prison. They created them in their own time, following a 10-week course of philosophy. But ‘course’ may be the wrong word for the series of philosophical conversations we have had with these men.

The images before us were created by a member of the first of our three groups. We have returned to the prison, several weeks after our final philosophy session, to view and discuss everyone’s work. We are standing in the same room in which our conversations took place. There is barely enough space for the 12 of us. There are only 11 chairs. The whiteboard still bears the shadows of the many stick figures that we drew and erased over the course of our sessions: figures which illustrated stories, puzzles, and ideas on topics such as happiness, personal identity, time, forgiveness and, of course, freedom. In some – but not all – cases, we used the board to summarise some influential theories or views on these topics. In every case, we offered the topic up for conversation, and we became participants in that conversation with everyone else.

The images before us were created by a member of the first of our three groups. We have returned to the prison, several weeks after our final philosophy session, to view and discuss everyone’s work. We are standing in the same room in which our conversations took place. There is barely enough space for the 12 of us. There are only 11 chairs. The whiteboard still bears the shadows of the many stick figures that we drew and erased over the course of our sessions: figures which illustrated stories, puzzles, and ideas on topics such as happiness, personal identity, time, forgiveness and, of course, freedom. In some – but not all – cases, we used the board to summarise some influential theories or views on these topics. In every case, we offered the topic up for conversation, and we became participants in that conversation with everyone else.

Of course, there are some significant differences between us and the men who choose to join us. Most notably, we go home after every session, but they do not. Moreover, we have PhDs in philosophy, and we have both taught the subject at universities. Although we have not surveyed the educational backgrounds of these men, it is unlikely that many of them attended university. It is reported that 47% of people entering custody have no formal qualifications (Prisoner Learning Alliance (PLA) submission to Education Committee Inquiry on Adult Skills and Lifelong Learning. July 2020), 42% have been permanently excluded or expelled from school (Ministry of Justice, Prisoners’ Childhood and Family Background. March 2012), and 57% of male prisoners enter custody with English literacy lower than that expected of 11 year olds (Ministry of Justice, Prison Education Statistics April 2019 to March 2020. August 2021). Prison learners are also more likely than the general population to require additional educational support: one third of UK prisoners identify on initial assessment as having a learning difficulty and/or disability (Dame Sally Coates, Unlocking Potential: a Review of Education in Prison. May 2016), with recent estimates of rates of dyslexia as high as 50% (Criminal Justice Joint Inspection. Neurodiversity in the Criminal Justice System: a Review of Evidence. July 2021).

Against this backdrop of educational disadvantage, it might seem surprising that the men in our sessions could engage in philosophically rich conversations, especially after only ten weeks experience of philosophy. But our conversations were deep and nuanced, almost from the very beginning, and the project work reflects this. We think that this can be largely explained by reference to our aims and the nature of philosophical conversation.

We ran these sessions on behalf of the charity Philosophy in Prison. The charity’s aim is simply to do philosophy in conversation, for no other reason than because we think that such conversation is good in itself. In her article in this issue (TPM 97), Kirstine Szfiris suggests that the dialogic nature of doing philosophy is a great equaliser. We wholeheartedly agree. Unlike others in this field, we have the luxury to focus on philosophy for its own sake, without any consideration of outcomes. And in doing philosophy, we are all on a level with one another.

Our ultimate aim, therefore, was always just to do philosophy, in conversation with one another. We were not trying to teach philosophy, although everyone – including us – certainly learnt a lot about it. We never required anyone to learn about famous philosophers or their arguments, and we included no tests or mandatory tasks in our sessions. We wanted only to talk about some philosophical problems, and to invite everyone to say what they thought about them too.

A great advantage of conversation is that it is open to almost anyone. Everyone in our sessions was able to say something meaningful about the problems that we introduced to them. They quickly got used to the sense of puzzlement that comes from thinking deeply about everyday concepts, and the licence that this gives us to offer up our thoughts and to disagree with one another. It just seems obvious, some of us thought, that a person can be momentarily happy, even in the midst of an unhappy life. Yet others among us thought it equally obvious that happiness must be an enduring, perhaps even life-long, state. We all implicitly agreed that this was a question worth exploring, and that we improved our understanding of it by listening to one another’s views.

Once we started thinking deeply about happiness, or about any of the topics under discussion, we became aware of two things. First, that not one person among us will ever fully understand the topic at hand, no matter their educational background. And, second, that we all share similar feelings when we try to improve our understanding. During our conversations, each of us felt confused, intrigued, sometimes amused, and often frustrated. Each of us came to understand that everyone else felt the same way. We all shared a common goal, and we knew that we could only progress towards it by trying to understand one another’s views as well as our own. We quickly got into habits of listening carefully to what others had to say, taking their suggestions seriously, and welcoming challenges to our own thinking. Without these practices, our conversations would have quickly stalled. And it is through these practices that we came to stand on an equal footing, by relating to one another as participants in a conversation rather than, for example, as teacher and student.

After only a few sessions, we began to hear some very positive things about the effects of our philosophical conversations. Some of the men told us that the sessions had helped with their social anxiety, their confidence, or their interest in education. One said that he had always tended to avoid disagreeing with others because, in his experience, disagreement generally became hostile or violent. He was delighted to find, in our sessions, a way of disagreeing with others that felt communal rather than antagonistic. Prison staff also reported a wider impact on the wing. Not only were the men from our sessions getting on better with one another, but they were also including others in philosophical conversations. Of course, we were very pleased to hear all this.

However, we cannot claim to have set out to achieve these aims. Indeed, we suspect that, if we had tried to improve the men’s lives in these ways, then we would not have succeeded. One of the most important aspects of our work is that we have no ulterior motive: we want nothing more than to introduce philosophical conversations into the lives of anyone who might be interested. We asked nothing of the men in our sessions that we were not prepared to offer ourselves. We took them seriously as philosophers, we said what we thought when asked, and we acknowledged the many times when we were confused or undecided about things. There was nothing more to our approach than this. Nevertheless, we have been very pleased to hear that so many of the men in this prison found, as we have also found, that doing philosophy can help them to improve their lives.

Following our discussion of freedom, inspired by the diptych and its two herds of deer, we move onto other presentations. We have only a little over an hour with each of the three groups, so our discussions are quick and lively. Several men have painted or drawn philosophically stimulating pictures. Some have written essays, and others have prepared verbal presentations, either on their own or in pairs. Some sing, rap, or recite poems. One man plays his guitar to explore the different kinds of happiness that music can evoke. Perhaps unsurprisingly, several projects explore freedom. Others address racism, moral relativism, knowledge, time, and the nature of philosophy itself.

As we talk about these topics, once again, we are repeatedly struck by the sheer quality and variety of these men’s philosophical insights. They have clearly returned to these topics again and again, whether in conversation with others or by thinking alone in their cells. We have little doubt that philosophical conversations will continue in this prison, long after we have returned to the comfort of our own homes.

Mike Coxhead has been doing philosophy in prisons since 2016. He is a Trustee of Philosophy in Prison and a Visiting Research Fellow at King’s College London. Mike’s research focuses on ancient Greek philosophy, particularly Aristotle’s epistemology.

James Chamberlain is a teaching associate at the University of Sheffield and the research associate at Philosophy in Prison. His research focuses on metaethics and the philosophy of David Hume. He started doing philosophy in prisons in early 2022.