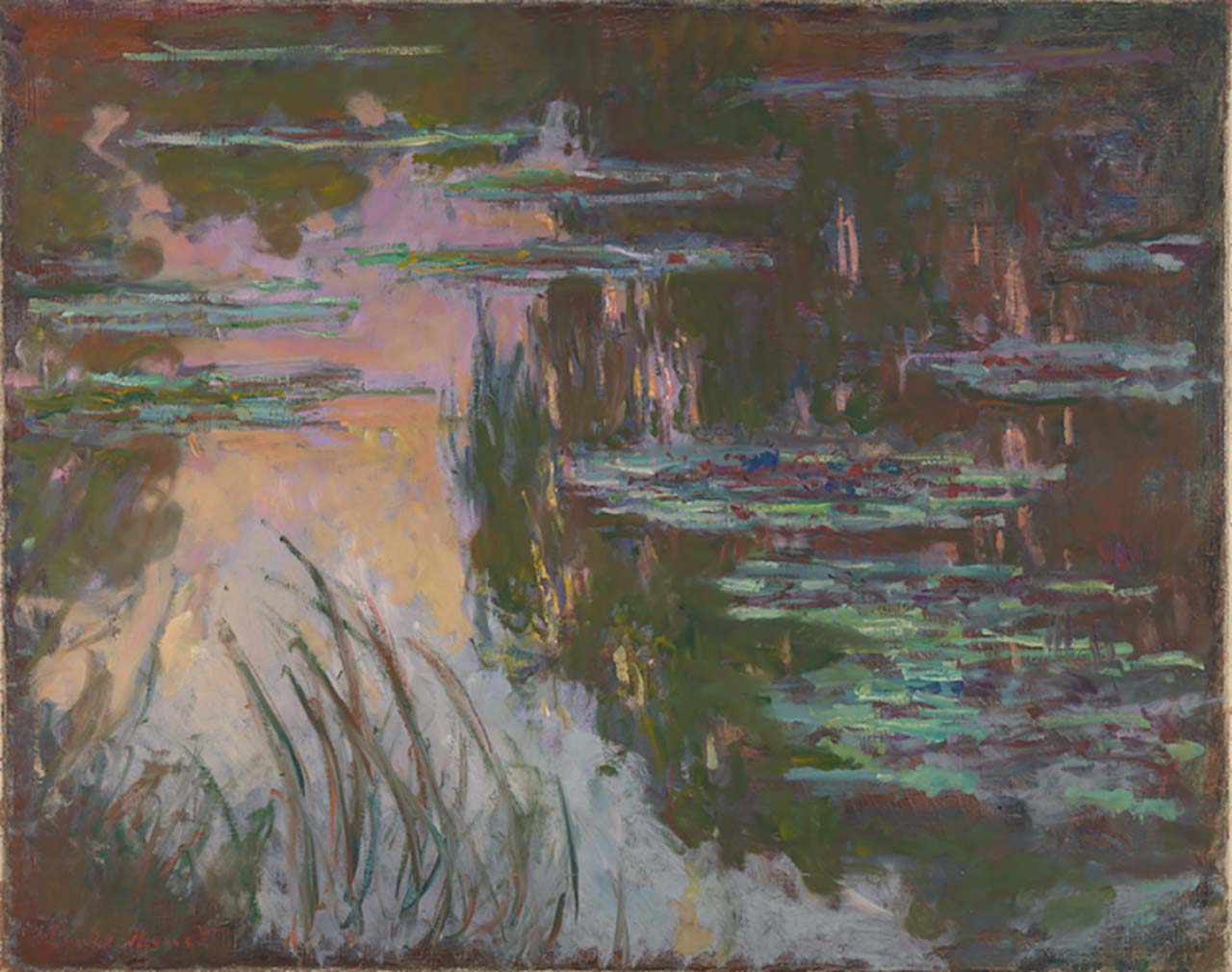

Many visitors strolling around the National Gallery savour the washed evening light, pinkly flowering across the still water in Monet’s masterpiece Water Lilies in Setting Sun. Some linger just a bit longer…and unleash something deeper from that pond. A sense of regret.

[Image: Water Lilies, Setting Sun, Claude Monet © The National Gallery, London]

[Image: Water Lilies, Setting Sun, Claude Monet © The National Gallery, London]

A small philosophical puzzle arises from this strange slip between seeing lily pads at twilight and seeing regret. We see the painted lily pads because they are depicted. But we can only depict things that can actually be seen (visible objects). Since regret is an invisible or private psychological state, it cannot be depicted. Philosophers treat this as a Howdunit puzzle: how is regret seen lurking in the lily pads and the dark downward reflections of the willow trees?

A first answer riffs off central cases. The picture looks regretful just as people do. But this doesn’t work for obvious reasons. When we see Jane as joyful, or Roger as regretful – we are connecting their look of joy or regret with a belief about them feeling joy or regret. But Water Lilies does not feel anything. We see the regret but we don’t believe the painting feels regretful.

A second and more interesting answer, is that we pre-consciously correspond the sensory features with affect, namely, regret. The Water Lilies is painted with a range of earth pigments – ochre, cadmium red, and ultramarine. These are darkened with raw and burnt umbers. These colours put us powerfully in mind of regret. Stephen Palmer, an academic psychologist, attests to it via empirical experimentation. Mitch Green, an analytic philosopher, provides a theoretical model envisaging the mechanics of it. They say attending to certain colours enables us to know how regrets feels. We use our own emotional state to empathetically mediate our way into the pictorial regret. The regret, in other words, is made visible by a felt mediation that draws on the information coming in through our eyes and locates what we see in an affective space.

Such views generate, to my mind, a more fundamental question. After all, regret cannot manifest independently of a regretful somebody. Regret is a sophisticated state and narratively rich. A sort of grief-riddled toxic glue holding us to a past we are not ready to give up. For my part, it was only once I knew of Monet’s obsessive interest in painting dusk in the garden while grieving his wife that I began to see the regret in this painting. I needed to see it as his regret to see the brackish bitter Verdigris broken up with tantalising notes of nostalgic amaranth tinged with the calm despair of cadmium light and shattered with screaming shards of naples yellow.

Which suggests that seeing emotions in pictures is not a Howdunit, but a Whodunit.

Dr Vanessa Brassey is a Visiting Fellow at The Faculty of Philosophy, King’s College London.

This piece was commissioned by TPM Contributing Editor, Dr. Emily Thomas.