July 31, 2025

What have academics to contribute to public debates?

On the evidence of the last several years, one could be forgiven for believing the central politically-relevant product of academia to be theoretical rationalizations for political positions that academics complacently accept on other, pre-rational grounds. Anyone who has encountered a conspiracy theorist online knows that sophisticated, apparently reasonable but really bizarre, arguments can be multiplied far more quickly than they can be refuted. That is a quite generic feature of argumentation: it is far easier to muddy the waters with a piece of ad hoc sophistry than to clean up the waters once muddied. For anyone who disagrees with contemporary progressive orthodoxy – on issues ranging from sex and gender, to Black Lives Matter and Defund the Police, to Covid lockdowns, to the feasibility of socialism – it is hard to avoid the impression that academics specialize in creating just this kind of public hazard.

Examples of this phenomenon abound. In particular, a common and easily recognized form that politically-fashionable academics’ interventions into political debates takes is the introduction of new negatively-valenced words and phrases for characterizing the deeds and dispositions of their opponents: “microaggression”, “implicit bias”, “mansplain”, “himpathy”, “white guilt”, “testimonial injustice”, “hermeneutic injustice”, “intersectionality”, “silence”, “privilege” and “gaslight” come immediately to mind, though there are many others. The effect of each such term is to create a presumption of guilt against those accused of it. Usually, the term is strongly implied to be associated with a well-supported body of theory, which it would be unsophisticated of one simply to dismiss out of hand. In this way, if and when accused parties fail to engage in detail with the theory ostensibly behind the charge to their accuser’s satisfaction, the politically fashionable seize the chance to paint them as forfeiting the intellectual high ground.

Such presumptions of intellectual superiority by the engineers of these myriad vices are unearned, and undeserved. In fact, many of the conceits just mentioned are not embedded in any well-developed body of theory. Recognizing this does not depend on disagreeing with the politics in whose support such terms are weaponized. To the contrary, approaching the problem with such vocabulary through the lens of politics would only serve to obscure it. For the issue is simple: it is that descriptions like “mansplain, “himpathy” and “white guilt” are inappropriately specific. They overtly build in restrictions to things that only men can do or only white people can be guilty of. But taken at face value, such restrictions are quite unnatural. Instincts to explain things, to sympathize and to feel guilt are extremely psychologically basic and widespread. They play a basic role in our psychological and emotional lives. The burden of proof is on theorists who want to argue that there is something very special – and specially bad – about how men explain things, how we feel sympathy for powerful men, or how white people feel guilt.

In other cases, though the terms in question don’t technically build in any restrictions, they are consistently applied in unprincipled ways. For instance, to take a notorious example, “microaggression” was only ever used to pick out small (alleged) violations of social norms in connection with race and sex. But again, that looks arbitrary. For instance, why shouldn’t the countless small ways in which conservatives are dismissed or ignored in academia equally count as microaggresions?

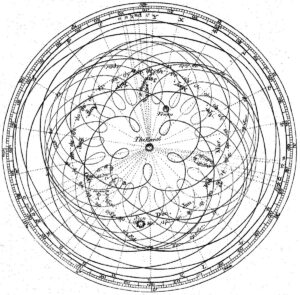

Theorizing that helps itself to more distinctions than it needs to explain relevant observations or patterns of behaviour is a very common form of bad theorizing. To be more precise, it exemplifies the methodological problem that natural and social scientists know as overfitting: over-complicating in order to fit unrecognized errors or biases. (Overfitting is explained accessibly and its profile generalized beyond mathematical modelling in recent work by Timothy Williamson, from whom I learnt about it.) Overfitting is what was wrong with refinements of the geocentric model of what we now know as the solar system. Because their model was built around the erroneous fixed point “the earth is the centre of the universe”, geocentric theorists were forced to help themselves to a grotesque number of epicycles, the extra loops in maps like these:

The mind-numbing complexity that one so often finds in academic theorizing about political questions can easily intimidate the average, non-academic reader into submission. Although one feels that there is something wrong with it, it’s hard to say exactly what is wrong—much, again, as it can be hard to say exactly what is wrong with the nauseatingly complex explanations of conspiracy theorists. Despite how much unhelpful vocabulary academia has contributed to public debates, it has some helpful vocabulary to contribute as well, like “overfitting”. When you come across someone drawing all sorts of arbitrary distinctions in the service of some political agenda, you shouldn’t be impressed. You should think “that’s overfitting” and you should picture the dizzying complexity of the geocentric model.

Although academics recently have largely been responsible for introducing invidious distinctions into public debates, it doesn’t have to be that way. Well-trained scientists and philosophers could use their expertise to identify and make vivid the methodological problems with such terminology. They could explain that it is not good science or philosophy on the part of their colleagues to pile distinction after distinction into the vocabulary on which they rely. In availing oneself of jerry-rigged notions like “white guilt”, one is reasoning in a way counter to the scientific spirit.

Countering the bad theories of their counterparts is not the only useful role for academics to play in public discourse. At their best, science and philosophy, conducted in a scientific spirit, are able to strip away the messy accretions of ordinary thought and reveal the core structure of some socially relevant phenomenon. An example is recent work by the philosopher Alex Byrne on the nature of the category woman. In a journal article and subsequent book, Byrne argues that to be a woman just is to be an adult human female. Isn’t that obvious?, one might wonder (provided, that is, that one antecedently agrees with Byrne). But in fact, as the extreme confusion of much of the public on questions of sex and gender illustrates, the average person’s pre-theoretical understanding of what it is to be a woman does not effectively equip them to distinguish between the essence of the category woman and contingent features associated with that category. One does not have to be a trans-activist to feel confused when it is explained to one that some biological males lack XY chromosomes, or that others – CAIS males – in effect go down the female developmental pathway from early in gestation. Don’t men, you know, have XY chromosomes and penises? Careful and rigorous analysis of the alleged problem cases is helpful for seeing how they can be reconciled with an austere, structural understanding of a woman as no more or less than an adult human female.

Here is another example of the kind of structural pattern that is made available by careful theoretical reflection. Many objections to simple criminal-laws like the “three strikes” rule depend on an aversion to punishing innocent people, or to punishing guilty people more than they deserve. One does not have to be at all “woke” to want to minimize the mistakes made by the criminal-justice system. But consider an analogy between practical mistakes of the kind the criminal-justice system makes when it imprisons someone who doesn’t deserve it and very simple perceptual mistakes, like mistaking one fruit for another. Clearly, such perceptual mistakes are inevitable if one is to rely on one’s senses at all. Given real-life human limitations, the only way to avoid ever falling victim to a visual illusion is to keep one’s eyes shut at all times—a cure far worse than the disease of sometimes making mistakes. Arguably, we should think of mistakes made in prosecuting criminals in the same way: much like perceptual errors, the only way to avoid them is by never prosecuting criminals—a cure far worse than the disease of sometimes making mistakes. Much more generally, we should recognize that humanly realistic systems—both perceptual systems and legal systems—enact a trade-off between accuracy and efficiency. That is a point that psychologists like Daniel Kahneman have explored in detail with respect to the nature of human thought. But arguably, it applies just as directly to human action too.

In short, good academics have at least two things to contribute to public debate. First, they can use their expertise to correct the theoretical errors propagated by their colleagues. Although it would be nice if such errors could simply be ignored, that is over-optimistic, because their veneer of sophistication makes them attractive to non-academics as well. In any case, there is no reason for those who reject aspects of contemporary progressive orthodoxy to cede the intellectual high ground to those who embrace it: that they are intellectually superior is one of politically-fashionable academics’ more irritating self-misconceptions. Second, in a more progressive spirit – that is to say, scientifically progressive – academics can help identify structural patterns in public and cultural life. The question that remains is whether any academics will have the courage to take up these tasks, or whether, instead, we are doomed to a permanently-polluted intellectual commons.

Daniel Kodsi holds a PhD in Philosophy from Oxford and is editor-in-chief of The Philosophers’ Magazine.